- Home

- Oscar L. Fellows

Operation Damocles Page 10

Operation Damocles Read online

Page 10

“God, we are hypocrites. Hypocrites of the worst land. We spent a fortune getting this far. If we weren’t going to do it, the money could have helped thousands of sick and starving people. We believed this would ultimately do them more good.”

“I can’t believe it,” said Conrad. “Forget what I said before. I like Leland, too. It’s just that he is the most level-headed person I have ever known. I cannot imagine him doing this.”

“He’s also the most pragmatic person you’ve ever known. All these months, we’ve been operating from an emotional perspective, in spite of being supposedly objective people. Leland wasn’t, and from a strictly objective viewpoint, he’s right. People are not going to take action unless forced to. It’s a matter of historical fact that populations never rebel until life is so miserable for everyone that the risk of death is preferable to living in slavery. It’s stupid, but that’s the human condition.”

“I know you’re right. I know we’ve been lying to ourselves, but Hector, in the end, we are scientists, not killers.”

“You’re using the same arguments I used to Leland, and again, I’ll ask you what he asked me: Weren’t you at Los Alamos during the 1950s, Conrad? Didn’t you collaborate on the H-bomb?”

“That was different.”

“Was it? Who created the neurotoxins and other chemical agents that the military has stored around the world? Remember Agent Orange, and mustard gas? We scientists have killed a lot of people over the years, Conrad, we just haven’t taken credit for it. Anyway, it’s pointless fretting and arguing. We can’t prevent it. He won’t bend. We can wash our hands and condemn him, or we can get busy implementing the plans we’ve spent so much time on. There are no other options.”

“But, Hector, the horizontal beam deflection circuit is still too wide. Minimum deviation is eighteen seconds of arc. Almost two miles. It will kill thousands unnecessarily. Can’t you dissuade him, Hector? He respects you.”

“I just tried. I pleaded until I was blue in the face, but he’s determined to go through with it, and he’s right. In order to succeed, he must fire now. The military is setting up a triangulation network using weather satellites to detect ionized particulates and water molecules as the beam penetrates the atmosphere. We’re delaying them by sidetracking parts shipments, minor sabotage and the like, but we can’t hold them up for long. We must fire before they complete their preparations. We can’t risk the weapon being found too soon. If it is, the plan will fail. Leland’s going to fire on the announced date, ready or not. In a way, I pity him.”

“Pity him? Why?”

“Because he is absolving us of guilt. He is taking the sin on his own head. He feels deserted by us, and terribly alone. Soldiers kill people in wars, but they are absolved of guilt by their country, their peers. Leland has no one, now. We chickened out.”

“But Hector, what about all those poor people? Millions of them. Women and children.”

The one named Hector cried out, “Damn you, Conrad! My heart is like a stone in my chest. I can barely breathe, thinking about it. What do you expect me to do? I don’t even know how to reach Leland.” He screamed into the phone, “What do you expect me to do? We all set this in motion. If Leland goes through with it, in five hours, millions are going to die, and there is nothing on God’s Earth that I can do to stop it.” The connection went dead.

XIV

At 8:00 a.m., Eastern Standard Time, on August 11, a peaceful Virginia countryside was beginning to warm under a reddish, rising sun. Dairy cattle were being turned out to pasture, fresh from the milking barns. Birds twittered and searched the field grasses for insects. Urban workers were just arriving at work, and beginning their daily routine. Lights and office computers were being turned on, coffee made, phones beginning to ring. The whine of motors started up in factories as supervisors and shop foremen began organizing the production tasks. Farmers were just coming in for breakfast, from their morning milking and feeding chores. The distant hum of traffic was beginning to pick up as the interstate highways filled with trucks hauling freight, and cars began plying the city streets.

Suddenly, across the tranquil Virginia countryside, a brilliant line of light appeared on the ground. A peal of thunder like the crack of doom shook the air, followed by a heavy, hollow drone that obliterated all other sound and feeling, immersing all living things in a sea of sonic pain. The earth quaked, and a curtain of dirt geysered skyward along a two-mile line that bisected Virginia from east to west, just north of and roughly parallel with Highway 64. The gigantic wall of erupting earth, jetting fire and smoke thousands of feet into the air, began advancing northward through the eastern United States at 1,600 meters per second.

As the invisible, ravening beam of energy advanced, lakes and rivers flashed explosively to steam. Concrete bridges and highways exploded into fragments as the moisture within their substance turned to steam and expanded, seeking a way out. Trees, grass, houses and other combustibles flashed into fiery gas and ash instantaneously. Superheated air near ground level expanded with an unimaginable thunderclap, followed by the deafening roar that trailed the racing path of destruction, sounding like a thousand gigantic jet planes breaking the sound barrier, then roaring away, the huge barrels of their jet exhausts resonating with the thrumming earth. A continuous concatenation of whip-cracking reports punctuated the deafening din, as electrical discharges flashed back and forth in the ionized, particle-laden atmosphere.

Outside the immediate burn zone, the fiery wind, created by air expanding away from the hellish heat of the beam, stripped the skeletons of buildings clean, like a child blows the down off a thistle. The earth heaved, and a shock wave traveled away in both directions—east toward Europe and west toward California—chasing the screaming wind. People actually saw it as it sped across the land, an uplifted, moving ridge, for all the world like a wave traveling through water, moving through the earth, buckling bridges and highways, shattering buildings twenty miles from the burn zone. Cars, trucks, buildings and people were bounced into the air. When they landed, some survived, and some were broken wrecks. It was as if a giant hammer had struck the elastic earth a single, prolonged, horrific blow. It left in its wake a wrecked landscape of broken trees, cracked highways and shifted rivers.

Sixty seconds after initiation, as the beam approached Alexandria, the weapon had measured orbital perturbation and map coordinates, and locked target coordinates into its fire control system. The beam began dancing across the heavily populated urban landscape, blasting selected buildings and installations into brilliant flashes of incandescent gas that turned to rising palls of black smoke. The smoke diffused into ragged curtains of gray as high altitude winds spread the dark clouds into tattered funereal shrouds, hanging above the land.

People over half the North American continent felt the tremor, though most of the serious damage was within ten miles of the burn zone. Fifty miles away from the path of the beam, the thundering roar was heard as a crackling sound, something like static on a radio, or the rattling gunfire of distant armies. McMurdo Station in Antarctica recorded the sustained seismic tremor that reverberated through the earth’s core.

From space, the event looked as if someone had scribed a pencil line in fire, across the eastern edge of the United States from Fredericksburg, Virginia, to Boston, Massachusetts; a line that immediately turned dark except for spots of fire here and there, where ruptured gas mains and underground fuel storage tanks continued to burn for hours afterward.

In seven and a half minutes, it traversed a zigzag path four hundred and fifty miles from Virginia to Massachusetts, a dotted line running through the government and financial sectors of Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Trenton, New York City, Hartford and Boston; slapping the smaller cities, towns and countryside in between. Gone were the great landmark federal buildings of Alexandria, Arlington, Washington, Gaithersburg, Rockville and Silver Springs. Gone, the wealthy enclaves of Georgetown, Long Island and Boston, and the military industries

in New Haven, Bridgeport and Portsmouth. Gone, the Pentagon in Washington, the Marine base and the FBI academy at Quantico, gone the Philadelphia Naval Yard, the Army base at Fort Belvoir and CIA headquarters at Langley. The great towered canyons of Manhattan were hills of smoking rubble. Nothing remained of the Manhattan peninsula but a blackened finger of land extending south from Harlem, to the confluence of the Hudson and East Rivers at Battery Park. Wall Street, the Stock Exchange and the Federal Reserve, the offices of the television communications and news broadcasting giants, the great banking and insurance empires—all gone.

Except for the Whitestone and Throgs Neck bridges, pocked and pitted Long Island was no longer connected to the mainland. Even the tunnels were collapsed. Save for the southern half of Staten Island, all five boroughs were without water and power. Newark and Jersey City were infernos, along with the refineries and industrial districts stretching up both sides of the Hudson River channel to Yonkers and beyond.

The actual burn swath was only two miles wide, but where the beam had touched, the line of heavy devastation was more than ten miles across. A million people died without knowing what hit them, vaporized in an instant, not even their bones remaining. Another three million lay maimed and injured in the shock zone on either side of the beam’s path.

Even though they had been warned, the stunned silence that characterized public reaction to the news was mute testimony to the utter disbelief that had existed across the nation. No one had believed it could actually happen.

East of the lakes and the St. Lawrence Seaway, fear was a palpable thing. These people had felt the mighty blow close at hand, staggered over the heaving, thrumming ground, felt the fiery breath of Hell’s own furnace, and now stared at skies dark with thick, roiling clouds of dust and ash. Electrical storms bubbled and frothed in the ionized atmosphere, lightning laced the black, tormented sky, and as the hours passed, the rising gases cooled and condensed, and muddy rain fell in torrents, flooding low-lying areas over forty thousand square miles. The destruction was complete. For all intents and purposes, the eastern seaboard was dead, from North Carolina to Maine.

###

Within hours, Army, Air Force and National Guard helicopters and troops were aiding local police and firefighters to evacuate casualties from the wrecked cities and towns along the edge of the burn zone. As the injured were brought out, victims in fifteen states overflowed into hospital emergency wards and temporary shelters. Medical teams directed the least critical patients to hastily erected field hospitals, comprised of army tents and house trailers.

The nature of the injuries were limited in range, which made the work of triage simpler. There were few cases of severe burns, and most of these were the secondary results of flammable materials igniting, not the direct energy of the beam. Those poor unfortunates directly in its path were no more. Vapors on the wind.

The preponderance of injuries were contusions and fractures, and those closest to the burn zone were naturally the most serious. Flying debris and falling structures had accounted for most of the critically injured. The blast wave had crushed and maimed, leaving many cases of internal hemorrhage and shattered ribs and limbs. Some were blind and deaf from the overpressure, bleeding from the eyes, ears and nose.

Within the burn zone, there simply was no life, and the vast area affected required response on a scale never before experienced. There were no rescuers to spare to search the nibble and torn earth within the zone on the remote chance of finding someone alive.

Within forty-eight hours, all the states west of the burn zone had mobilized rescuers and emergency medical teams, and the roads and highways leading into the midwestern towns and cities were jammed with traffic. Airports and railway stations were crowded beyond capacity with incoming volunteers and those trying to leave.

News reporters descended like vultures to carrion, harassing the stricken crowds, shoving microphones into the faces of mind-numbed, floundering people. They haunted airports and railway stations, TV crews and equipment often impeding the flood of people trying to exit or gain entrance.

Surprisingly, there were relatively few people fleeing the area. If there had been more, total confusion would have prevented the aid from getting through. It was as though they were stunned too senseless even to flee, or else assumed that the danger was over. Some of them later said that they were in such a state of shock, or so caught up in the rescue efforts, that the thought of running away never occurred to them.

The major broadcast television networks were off the air for an hour and twenty minutes after the strike, as customary uplinks were rerouted to affiliates in Atlanta and Chicago. These cities became the news centers of the nation in the days that followed, and Atlanta, because of its hub airport, warmer climate and convention facilities, became the pro tempore seat of federal government. Almost a third of the U.S. Congress was missing and presumed dead, and some agencies’ headquarters staffs were completely wiped out.

Government offices were being set up in crowded federal, state and city buildings, and in rented hotel suites and commercial offices across Atlanta. Some were even put in conscripted warehouses and industrial space. School auditoriums, university conference rooms, ballrooms and public theaters were being used as impromptu meeting places for working committees and conferences of federal, state and city officials. Federal law enforcement and military personnel were arriving hourly to replace missing Justice Department and Pentagon commanders.

###

One week after the holocaust, a third tape was delivered to the Los Angeles television station that had received the first tape. Needless to say, it was taken seriously this time, and it was broadcast. The voice was the same, and the message was short: “You have thirty days. If you do not comply by September eighteenth, I shall begin destroying strategic target areas all across the United States. I shall not identify those targets, lest you lose sight of what you must do, in your efforts to flee. Flight is pointless. What I demand is simple, and easily done. I had hoped that you would listen, but knew in my heart that you would not. You have your proof. If you do as I tell you, you will be all right. If you do not, heaven help us all, for I shall not stop until you submit. Not if every living thing has to die.”

The public went insane. Public officials were attacked and killed on the street. Some were dragged from their homes, along with their families, and put on buses going anywhere, with nothing but the clothes on their backs. In Atlanta, 2,500 people were killed—police, congresspeople, national guardsmen and civilians—and thousands more were injured in city riots. L.A., Chicago, Houston, San Francisco, Denver and St. Louis were crippled by chaos as federal buildings were ransacked and burned, and their inner cities became war zones. State capitols fared much the same.

Within three days, amid a nationwide clamor from the public, a working group among the remaining members of the House of Representatives had drafted a bill titled “The Governmental and Educational Reform Act,” which reiterated, almost word for word, the ten commandments laid down, and four days after the taped message, they passed it unanimously. The Senate passed it the same day, and the following morning, an embittered but silent President Vanderbilt signed it, without ceremony, into law. It was later rumored that he had broken the pen he used, and thrown the pieces on the floor.

State and city governments reluctantly followed suit, and public buildings were awash with people bustling to and fro, cleaning out desks and destroying records, a skeleton staff watching as others dumped the memorabilia of their careers into trash cans, and left the buildings forever.

XV

It was the second week in September, and the remains of Broderick’s group now consisted of seven operatives. They were currently encamped in a Miami Beach hotel. His secretary and the other agents, in fact everyone stationed at Langley, Virginia, who hadn’t been away on assignment or vacation when the weapon vaporized it, were presumed dead.

His operation was still being funded, although the routing of the funds

had changed. New payroll accounts had been established by the White House, on some bank in the Cayman Islands, and they were being paid via letters of credit that established individual trust accounts at a Miami bank.

It was 11:30 p.m. on a rainy, overcast evening. Broderick sat on a sofa, smoking a cigarette and surveying the second-floor room they were using as a ready room. It was littered with dirty Styrofoam coffee cups and overflowing ashtrays. Telephone and electrical cables ran across the beige-colored carpet in all directions, connecting four telephones, three computers and two printers.

A copier stood against the wall where another sectional sofa, a chair and two end tables had been pushed, clearing the center of the room for two long, tubular-steel folding tables that were pushed together in a “T” arrangement. Two of the computers sat on opposite sides of one of the tables, and the rest of the surface area was covered with papers, maps, and litter from vending-machine coffee and take-out meals. A half-dozen straight-backed chairs stood in disordered array around the tables.

James Reed was in Indianapolis. His assignment there was to kill Beverly Watkins, and through her death, to send a warning tremor through the media grapevine. An attention-getter to let them know that things hadn’t changed where it counted.

Broderick’s mouth tightened, as it did every time his mind turned to Reed. Reed was a dangerous bastard. The easy stride, slow drawl and laid-back mannerisms were a learned subterfuge, meant to throw people off—make them underestimate him. Broderick wasn’t having any. He was an experienced judge of men, and he could see it in the way Reed moved. He was lithe, and strong, and fast.

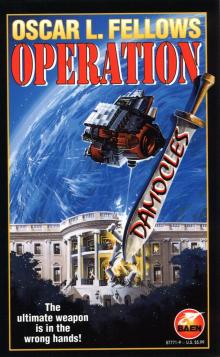

Operation Damocles

Operation Damocles