- Home

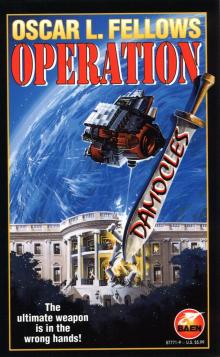

- Oscar L. Fellows

Operation Damocles

Operation Damocles Read online

Table of Contents

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII

XXIX

XXX

XXXI

XXXII

XXXIII

XXXIV

XXXV

XXXVI

XXXVII

XXXVIII

XXXIX

XL

XLI

XLII

XLIII

XLIV

XLV

XLVI

OPERATION DAMOCLES

OSCAR L. FELLOWS

Baen

So began "Operation Damocles", a secret military mission to kill a super-weapon, and the battle for domination of the Earth. Meet a spy with human failings and a pragmatic sense of duty. Meet the woman he's ordered to kill, a newscaster with the courage to defy a media gag-rule and speak out. Meet a crotchety old rascal of a scientist, and his lifelong friend, a kindred curmudgeon and retired CIA agent -- together they engineer a world-wide rebellion. Meet an idealistic scientist willing to kill millions for his vision of liberty. And last, meet a powerful president who's willing to commit treason and mass murder in order to regain power, and a vice-president with the courage to oppose him. Political corruption, conspiracy, treason, CIA spies and an obsessed patriot determined to cure the world or kill it, they are all here. It may surprise you, which side you're on…

PANDORA’S BLACK BOX

“Don’t you think we should investigate a little more before getting Headquarters in a tizzy? It could just be a simple mistake.”

Dykes stopped pacing and faced Castor. “How? Think about it, Charlie. How could it possibly be just a simple mistake?” Dykes ticked off points on his fingers. “A module the exact size and weight of a legitimate package gets substituted on a shuttle flight. The module has the correct number stenciled on it. It must have even had an inspection tag on it, now that I think about it, otherwise the packing crew wouldn’t have loaded it. The launch manifest lists the package for that flight, on that date, when the real module is not scheduled to go up for another nine days. The mission manifest, which is a duplicate copy of the launch manifest, is generated by the same person at the same time, yet the copy Kennedy has is different from what we have. The real module wasn’t even in Inspection then, it was in the warehouse. The warehouse didn’t pull it, Inspection didn’t inspect it, no other package is missing and we can’t find it in orbit, but we sure as hell put something up there.”

Realization dawned in Castor’s eyes, and his face blanched. “You’re thinking some kind of terrorism, aren’t you? My God, Joe! What could it be?”

Operation Damocles

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 1998 by Oscar L. Fellows

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

A Baen Books Original

Baen Publishing Enterprises

P.O. Box 1403 Riverdale, NY 10471

ISBN: 0-671-57771-9

Cover art by Gary Ruddell

First printing, October 1998

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Typeset by Windhaven Press

Auburn, NH

Printed in the United States of America

eISBN: 978-1-62579-383-6

Electronic Version by Baen Books

www.baen.com

To the times and the country of my father—an America of conservative values, individual liberty, common courtesy, public decency and respect for the rights of others.

I

Columbia sat on the launch pad, nose to the blue-white Florida sky, vapor from her tank vents drifting and dissipating on the light, intermittent breeze. Her crew was aboard, and the gantry elevator had just been secured in preparation for launch. Inside her instrument panels and bulkheads, signals raced through electronic pathways of printed wiring as circuit diagnostic programs searched for faults.

From a bird’s vantage point, technicians in white coveralls appeared like ants as they moved around the base of the gantry and the huge spacecraft. The temperature was rising on another humid June day, and the low-lying mist was burning off the backwaters of the inland, marshy estuary known as Mosquito Lagoon.

To the west, occasional palmettos, moss-laden oaks and windrows of salt-cedar trees interrupted the flat, hazy horizon of low scrub that was Merritt Island Wildlife Refuge. There, alligators, snakes, armadillos and marsh hawks were wrapping up a night of foraging, and settling into their cooler nests and burrows in anticipation of the sluggish heat.

On the eastern side of the launch complex, along the Atlantic shore, the surf frothed and gurgled among the gently lapping waves and low rollers that marked the transition between tides. It was a peaceful summer morning at Kennedy Space Center. The scent of the sea rode the easterly breeze, and the shuttle launch preparation in progress was unremarkable.

For Mission Control, this flight, like a hundred previous ones, would be a routine, even humdrum mission, entailing three onboard science experiments, deployment of an ultraviolet astrophysics research satellite, and two term experiments that would be inserted into a decaying orbit—an orbit calculated to assure destruction upon reentry. “Term packages” were neat, clean—no additional space junk. They did their thing and disappeared, and they did not require the extensive application process required to secure a permanent orbit assignment.

“Fifty-seven minutes to ignition sequence,” echoed the gantry loudspeakers. The gantry technicians continued their tasks with no apparent notice.

Inside Launch Control, launch team personnel were just as cool and professional, running through the diagnostic routines in methodical, workmanlike fashion. Launch Director Gene Obermiller walked between rows of technicians and engineers seated at computer monitors. He looked over their shoulders at their CRT displays, stopping occasionally to listen to the two-way conversation between a member of the shuttle crew on board Columbia and one of the technicians as they ran through the prelaunch systems checklist.

An hour from now, most of the people in Launch Control would leave, and Mission Control in Houston would take over flight operations. In nine days, assuming no technical difficulties or inclement weather, they would do it all over again for Atlantis.

“Launch telemetry ready.”

“Goldstone, do you copy?”

“Are you gonna catch the game tonight?”

“Three is vented, you can disconnect,” went the drone of quiet conversation across the room.

“Minus forty-three and counting at oh nine oh five,” the annunciator echoed.

The sky and sea seemed quietly expectant today. In a few minutes, the fuming vehicle on the pad would ride a coruscated column of water vapor and white-hot flame into those boundless vaults of air, pirouetting gracefully as she performed her dance with destiny, and Merritt Island and the Cape Canaveral peninsula would vibrate to the crackling thunder of her engines.

Obermiller looked at the ceiling monitor that displayed the down-range horizon, ran his fing

ers through the dark hair that was beginning to gray above his temples, and massaged the knotted muscles in the back of his neck.

Taciturn by nature, Obermiller was unusually quiet and introspective this morning. His colleagues liked his poker face and unfailing dependability. They respected him as only one veteran can respect another. In engineering vernacular, Gene was positive-displacement. You knew what you were getting and you always got it.

Long ago, someone had laminated a newspaper cartoon and pinned it to the corkboard inside the glass-covered bulletin board in the lobby of the Launch Control complex. The person who had clipped it and penned in “Gene” with an arrow pointing to one of the characters was long forgotten, but the sentiment lived on in the minds of NASA old-timers. The labeled golfer in the cartoon leaned casually on a golf club, watching an atomic mushroom rise above a nearby city skyline, and said to the other golfer, “Go ahead and putt, Ralph, it’ll take a few seconds for the shockwave to reach us.”

That was Obermiller. The consensus was, if Gene ever got nervous, you might as well bend over and kiss your nether region good-bye, because you were about to witness the Second Coming. It wasn’t that evident on the surface, but today Gene was nervous.

Forty-seven minutes later, “SRB separation at oh nine fifty-two,” came the voice of the controller. “She’s seventy-five miles downrange and five-by-five. Seven minutes of burn remaining.”

A seated technician looked at Obermiller, who stood watching the overhead monitor. “Bermuda has comm and telemetry, Gene, and Sydney is standing by for the handoff.”

“Fine. It looks like a good one,” Obermiller replied.

###

Two days later, Columbia orbited the Earth belly down, her bay doors open to eject her payload toward a higher orbit. Two mission specialists worked in the cargo bay, intent on their task, oblivious to the black, yawning void above them and the majestic, blue-white, marbled planet turning below. The rest of the crew was busy inside Columbia’s cabin.

When the research satellite was away, controllers on the ground would fire thrusters on the “bird” to maneuver it into geosynchronous orbit 22,300 miles above Earth. Once her payload had been deployed, Columbia would roll over on her back, open bay toward the Earth, for her remaining days in orbit.

The important payload, the ultraviolet research satellite, was gently guided onto the spring-driven expulsion platform by the two mission specialists, and when the moment was right, ejected in a slowly spinning trajectory, like a rifle slug, toward the deep. The two remaining orbital experiments followed, lifted from the shuttle bay and released in Columbia’s wake by the robot arm, with just enough rearward momentum to assure they cleared the shuttle’s vicinity, where engine and thruster maneuvers might affect them. As the astronauts watched past the tail of the ship, the instruments shrank to specks of light, and finally winked out in the distance.

“Payload insertion complete,” radioed the mission specialist to the shuttle commander.

“Good! Secure for maneuvering,” came the reply.

At two days into the mission, everything was going fine. Columbia would spend three more days in low earth orbit (LEO) as the crew completed the onboard experiments and other studies that comprised this missions program, then, due to impending weather at Kennedy, she would land at Edwards Air Force Base in California. There, she would be mounted on the back of a 747 jetliner for transport back to Kennedy.

II

Mission Control at Johnson Space Center was located in building #30, one of a hundred or so buildings that comprised the sixteen-hundred-acre Houston site. Most of the JSC installation consisted of administrative space and laboratories, with only a few core facilities actually dedicated to astronaut training and mission operations. As a senior NASA official once remarked, “NASA could put the giant fifty-story Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center on the moon if it wanted to, but there were no rocket engines made that could lift the paperwork required for the project.”

Building #30 was a sprawling structure surrounded by grass, walks and a few trees. Large picture windows in the outer offices looked out over a flat, hazy vista that stretched eastward toward Galveston Bay, and southward toward League City and the Highway 45 expressway. Structures and trees cast sharp, contrasting shadows in the glaring, afternoon sun of a Texas summer day.

Inside, the chief of Mission Control was in the midst of receiving an unsettling piece of information. Big and craggy-visaged, Joe Dykes sat with customary ease behind the wide, executive desk in his fourth-floor office, his back to the expanse of plate-glass window that looked out on the courtyard, the horizon and the cloudless blue vault of the sky. Cool-white fluorescent lighting lent a supporting ambiance to the gray carpet and white walls which were intermittently demarcated by beige metal furniture, potted plants and framed commemorative plaques. It was a pleasant, air-conditioned haven from the sweltering outdoor heat.

Across the oak-grain expanse of his desk, with its neatly organized stacks of paper, Dykes regarded Mark Miller, the Flight Operations Chief from Mission Control, with a quizzical expression. Both men were dressed in shirt sleeves and ties, and looked a bit lost sitting in Dykes’ spacious, but spartanly furnished office.

“What do you mean, lost it?” asked Dykes.

“Exactly that. Two term packages were placed in orbit; now one is there, and the other has vanished. We rechecked the record tapes from the shuttle. Insertion acceleration moments are within a couple of gram-seconds of one another. Unless one got hit by a piece of orbital debris, it ought to be there.”

“Think that could have happened?”

“I don’t know what to think. If it got hit by something, it should be spinning on an erratic path, or at least have left bits and pieces that would be easy to find. So far, not a thing. We haven’t given up. We’re still scanning the orbital track, but I thought you ought to know, just in case the customer calls up and wants to know what’s going on.”

“Whose was it, do you know?”

“No. No names on my paperwork, just the package numbers, vectors, insertion times, etc. We’re just trying to do our routine confirmation of deployed payload. Found the first one right away, right where it’s supposed to be, but we’ve been looking for the other one for twenty hours now. Nothing. Not even gas.” Miller rose to go. “I don’t know what else to tell you at the moment, Joe. I’ll let you know if it turns up.”

“I’d appreciate it, Mark. Thanks!”

“Sure thing,” said Miller as he turned and left through the open doorway.

Dykes picked up the phone. “Denise, get me Bobbie-Jo Hendricks in Customer Relations, please.” A moment later, “BJ, I may have a problem. We lofted two term packages last week, mission twenty-eight, Columbia. One has gone missing. Can you find out whose they were, and points of contact with phone numbers? Yeah, as soon as possible. Thanks!”

An hour later, Dykes sat mystified. He had learned that the missing experiment was officially listed by Kennedy as a pyrolytic metals experiment from the mechanical engineering department at Stanford University. However, Mission Control hadn’t communicated with Stanford, as they ordinarily would have, in order to notify them when insertion was completed and transfer of responsibility had taken place. The reason for the glitch was that there was no mention of the experiment in Houston’s flight operations plan. In fact, it turned out that Stanford’s package hadn’t flown on Columbia, and according to the university, was scheduled aboard Atlantis, slated to launch the following day.

The packing crew at Kennedy had a manifest which indicated they had loaded the Stanford module aboard Columbia, but the Kennedy Payload Inspector, whose signature was on the manifest, said that he had inspected only one term experiment for the Columbia mission, a module belonging to Argonne National Laboratory, and denied having signed a manifest for the Stanford package. He was aware of the module from Stanford, confirmed that it was scheduled for Atlantis, and that it was presently being inspected.

&nbs

p; ###

The following day, Dykes spoke with Charles Castor from Customer Relations, who had been investigating the incident.

“If it’s an alloying experiment, why is it a term package,” asked Dykes. “Don’t they want the finished melt back for study?”

Castor was a slight, middle-aged man who had the natural ability to look comfortable in a suit. He resembled the rumpled college professors in Walt Disney films who always look at home wearing tweed jackets with elbow patches, a sort of born-to-it, casual look. He always seemed to go through a kind of physical ritual before he said something, as if talking somehow required a particular body position. Dykes thought that perhaps he just used the time to collect his thoughts.

Castor adjusted his glasses, crossed his legs, laced his hands together around his knee, adopted a serious mien, and responded, “The project description states that the hydrogen torch that fires the kiln, and the attendant outgassing from the metals, make it potentially unsafe to perform this particular experiment on board the shuttle. The design parameters for the experiment were all set up through NASA engineering. Because of that, the standard volume limit for experimental modules was extended to two cubic meters so that cameras, telemetry antennae, a spectrometer, a gas chromatograph and a heavy testing machine for hardness, malleability and other final properties could be included. It has much larger gas bottles, and an attitude control system. It has a CO2 inventory for propellant, and a guidance system of sorts. Telemetry and transceiver frequencies have been cleared; everything is copacetic.

Operation Damocles

Operation Damocles