- Home

- Oscar L. Fellows

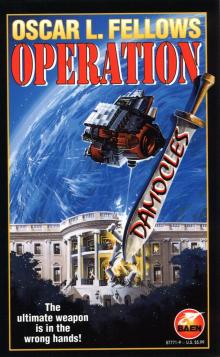

Operation Damocles Page 2

Operation Damocles Read online

Page 2

“Dr. Haas at Stanford is ticked off about all the questions. He says that all the preparations were done months ago, and whatever foul-up we have made, it has nothing to do with his package. He wants to know if his schedule is going to slip because of this.”

Dykes waved his hand dismissively, got up and paced the room. “Tell him no. Tell him that the package we launched was simply misidentified somehow, and that his experiment can go as scheduled. The big questions now are, what did we launch, and why can’t we identify whom it belongs to? It apparently fit the Stanford module dimensions closely enough that the packing crew loaded it without a bleep. All other scheduled payload has been inventoried and accounted for. Nothing is missing. Surely someone didn’t just package a couple of empty oil drums in a payload module, and risk losing a job for a practical joke. It just doesn’t make any sense.”

“Whatever it was, it wasn’t empty drums. It massed at four hundred and eight kilos.”

“Why didn’t they catch that? Isn’t that a lot for an experiment package?”

“Yes, but like I said, special clearance was obtained.”

Dykes’ face showed surprise, doubt. “You mean, the Stanford experiment weighs the same?”

“To the kilo.”

“Isn’t that just the weight shown on the manifest?”

“No, Joe, the packing crew weighs all payload before stowing it for launch. That is the mass the crew chief logged at the time the package was loaded.”

Dykes simply stared for a moment, then said, “A chill just went up my spine. It’s beginning to sound like this was a very deliberate, well-planned substitution. The odds of two random packages having exactly the same weight and dimensions are astronomical.” Dykes thought a moment. “I’m going to call Clarence Patterson.”

“Don’t you think we should investigate a little more before getting Headquarters in a tizzy? It could just be a simple mistake.”

Dykes stopped pacing and faced Castor. “How? Think about it, Charlie. How could it possibly be just a simple mistake?” Dykes ticked off points on his fingers. “A module the exact size and weight of a legitimate package gets substituted on a shuttle flight. The module has the correct number stenciled on it. It must have even had an inspection tag on it, now that I think about it, otherwise the packing crew wouldn’t have loaded it. The launch manifest lists the package for that flight, on that date, when the real module is not scheduled to go for another nine days. The mission manifest, which is a duplicate copy of the launch manifest, is generated by the same person at the same time, yet the copy Kennedy has is different from what we have. The real module wasn’t even in Inspection then, it was in the warehouse. The warehouse didn’t pull it, Inspection didn’t inspect it, no other package is missing and we can’t find it in orbit, but we sure as hell put something up there.”

Realization dawned in Castor’s eyes, and his face blanched, “You’re thinking some kind of terrorism, aren’t you? My God, Joe! What could it be?”

“Shoe-box nuke maybe, or some kind of bio-weapon. Either one could kill a couple of million people if placed just right. Maybe nothing more harmful than half a ton of propaganda leaflets. Lord, what a coup that would be for one of these lunatic outfits. I just can’t think of a practical reason for doing something like that from space, unless the main intent is to embarrass NASA and the U.S. government.”

Dykes picked up the phone. “I hope I’m wrong about all this, but I’m calling Patterson. Get all tracking stations busy trying to find that thing. Notify NORAD and the Air Force Space Command that we need their assistance in finding an experiment module that strayed off course. Give them dimensions, trajectory and last known coordinates. Do not tell anyone, there or here, what we have been talking about, okay? Not even your wife. If the media gets wind of this, the agency will be crucified, even if nothing bad ever comes of it.”

III

Dr. Clarence “Butch” Patterson sat in his office looking through a water-streaked, plate-glass window at the Washington, D.C., skyline. It had been raining, and right now it looked as bleak and overcast as a winter day. It matched his frame of mind.

Patterson looked the part of the distinguished scientist and administrator that he was. He fit the public image. In some part, that fact had aided him in his rise through the National Office of Science and Technology, and through NASA. Not that he wasn’t a good scientist, he was, and a good administrator too, but he had learned long ago that he had a flair for office politics. His was a natural, untrained charm—an easygoing personality that instilled confidence and trust. The crinkle at the corner of his eyes when he smiled, the automatic conspiratorial wink he unthinkingly injected into every conversation with peers and subordinates alike—these were habitual traits that made people feel warm and personal with him, as if they were his closest confidants. He was well-liked by most of his staff and associates, and worshipped by the secretary of ten years whom he had taken with him in his last two promotions. He was generally known for his honesty, ready smile and laid-back nature. He wasn’t smiling now though, and the unusually accentuated lines of his face made him look considerably older than his fifty-five years.

To Patterson, the position he had attained this past January, as Director of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, was the epitome of career achievement. It was his life’s ambition, and it had come true. It meant that his name would be added to the annals of human history. His life had mattered. He had helped to shape the world and left a legacy that people of future generations would read about. He loved the stature, but God, he hated the social scene in today’s Washington.

Nothing he had ever done had prepared him for the life of a Washington bureaucrat. It was insane. interoffice spying was routine. It was like a pack of rats, scrabbling for an advantage, and woe unto him who let his guard down. Not even your own staff could be trusted beyond a certain point, he thought. You certainly didn’t build intimate confidences.

The work he had trained for and loved all his life—agency business—was suddenly of secondary importance to everyone but him. Petty incidentals were all that mattered. His calendar was filled with important meetings about trivial stuff—protocol alerts concerning visits from minor VIPs and foreign dignitaries, and innumerable state functions with which he had nothing to do—and it seemed that the only thing ever accomplished at those meetings was establishing the time and elate of the next meeting.

He was learning that, unlike science, nothing in cabinet-level politics was straightforward. Politics, to Patterson, was an elemental thing. It was making people like you. It was an emotional thing that worked best when it was a natural gift, as it was with him. A kind of subliminal cajolery that swayed most people, and if applied over time, eventually got you what you wanted. He knew what he was doing, and when he was doing it; it wasn’t totally unconscious. He picked his targets, people who could give him a leg up on his career ladder, and he knew that he wasn’t quite the sincere and caring man he pretended to be. The inner man wasn’t particularly proud of himself, but he also knew he didn’t belong among the blatant brotherhood of thieves that made up the woof and warp of Washington’s social fabric, Washington was a place of grand buildings and edifices, monuments to great ideals, but these days, it was peopled with all the utterly selfish of the land. Here, the only aspect of government business that mattered was who profited from it. Office politics consisted of getting the dirt on other people, even amplifying on their minor mistakes, while keeping one’s own transgressions safely hidden.

In a way, he felt ashamed of his ingratitude. The newly installed President Vanderbilt had personally appointed Patterson, lifted him above his equally deserving colleagues and peers in the space sciences community, and set his name down in history. Lately though, the first flush of pride and pleasure in the appointment was waning, and he had begun wondering, why me? He had been director of the Johnson Space Center at Houston, and as such, certainly in line for the position, but somehow it just didn’t feel

right. In the past few months, he had come to understand that everything done in Washington was done for a reason other than the one publicly expressed. If someone benefited, a payback of some sort was generally taken for granted. Vanderbilt had shown no reticence in pointing it out.

Patterson hadn’t “known” anyone in particular. He knew that Vice President Joseph Miller had lobbied for his appointment, but he didn’t know why. He had never met the man. Why had Miller championed him? Why had Vanderbilt acceded? Had he just slipped through the cracks? Was his appointment an accident, a decision made by a man who was tired of thinking about all the minutiae of moving into his office, and who momentarily had no better candidate in mind? If not, if there was a hidden motive, what payback was expected?

It had begun to haunt him. A niggling doubt that hovered always on the fringe of consciousness, clouded his perspective, pulled his thoughts aside, inhibited the clear, free-flowing logistical thoughts of mission, people, tools and money that he was used to. His dream had begun turning sour.

And now this! Only six months into his administration, and out of nowhere, Joe Dykes had handed him a political hot potato to top them all. His dream of a long and productive tenure was rapidly becoming a nightmare of being the first NASA chief to be fired in disgrace.

“God, let it be just another paperwork foul-up,” he prayed. “Just another innocent package that got coded wrong and pulled by mistake.”

He didn’t believe it, even as he thought it. As Dykes had said, there were too many matching factors for it to be coincidental. What would his historical legacy read if NASA had unwittingly orbited a weapon of some sort, someone else’s weapon, to be used against the United States? And how to react?

In a normal environment, it was his duty to tell the President. The Commander in Chief should be informed of any potential threat to national security. But these days, it wasn’t a normal environment in Washington. He had seen enough heads fall in the past six months to know that if he told the White House, it would be on the evening news. Not even a ghost of a doubt. The first thing they would do is wash their hands and make him the sacrificial goat. Even if it turned out to be some sort of innocent error, he would be painted a fool, at the very least, and his career finished.

If he was a heartless bastard, he could “uncover” the foul-up himself, and destroy the lives of a few select people in the agency to save himself. He couldn’t bring himself to do it. NASA and its people had been his life, and he loved it too much to subject it to that kind of fallout. Security would get so tight that a person wouldn’t be able to visit the bathroom alone, and the already paper-mired process would become so impossible that NASA couldn’t launch a paper clip. It would filter out into all the support contractors and research groups until nothing substantive would get done. The agency would become just another budgetary black hole, and might even end up as part of another agency consolidation as Congress put on one of its shows of austerity for the American public. They might even put it under military command. It was already regulated by the military to some degree.

He had admonished Dykes not to let the news leak, and he thought he could rely on him. With that thought, his resolve hardened. He would keep it quiet until the issue went away, or blew up. He would be no worse off in any event. He wasn’t about to carry an ax over to the White House and bare his neck.

IV

Harold Tanner, newly appointed Secretary of Defense, was similarly preoccupied in the headquarters building at Langley Air Force Base. He had just come out of one of the strangest and most depressing meetings of his career, and now stood at a window in the spacious, third-floor officers’ lounge.

Against government edict, he was smoking a cigarette indoors. He stood in a habitual attitude of military parade-rest, his feet apart and firmly planted, his hands locked behind his waist, cigarette between his fingers. He surveyed the pedestrians in their glistening plastic raincoats, their umbrellas bobbing along the sidewalks, and watched the metronome beat of windshield wipers in the slowly moving traffic along the main base boulevard.

His crew-cut hair, humorless gray eyes and weathered face, along with the posture of his spare military frame, looked out of place in the tailored gray suit. Though he did not move, there was no mistaking the anger and agitation in him. His rigid stance, the nervous flicking of the cigarette and the scowl on his countenance forewarned anyone who might have contemplated speaking to him.

Tanner had just carried out an order to reassign two highly experienced and successful commanders from the U.S. Air Force Air Combat Command to assignments that were an insult to their skills and abilities. He hadn’t realized what was happening until he met and talked with the two officers. As a former War College professor, he couldn’t fathom the reason for such a move, and as the new kid on the block, he knew he would get the blame for it among the services.

The Vanderbilt administration had jumped into Washington politics with both feet, and the walls inside the Beltway were still reverberating. The deal-making and back-room bargaining had gotten under way with a vengeance that shocked even the jaded insiders of Washington society. Government programs and agendas were changing in ways that seemed mysterious, unconnected and illogical. Agency heads were toppling like dominoes, and bureau reorganizations were becoming commonplace.

People connected with government business, from defense contractors to those in financial institutions, were wondering at the surprising trends in corporate America. In New York City, key industry and financial managers were retiring, and second-string media people were quietly vanishing into other pursuits—even into other countries. Tanner knew that the public wasn’t aware of these behind-the-scenes happenings, but he assumed they had noted the replacement of the odd network newscaster and television news-show host. It was as if Vanderbilt was assembling a team that encompassed far more than just the Oval Office.

And so many deaths! Vanderbilt had attended more state funerals in the first six months of his administration than any previous president. Two of the Joint Chiefs were dead. Admiral Poindexter and General Thompson had died together in a freak automobile accident in February. Patrick Monahan, Under-Secretary of Commerce, was killed by a guerrilla missile that downed his plane during a visit to Nicaragua, in March. Susan Kawalski, U.S. Deputy Attorney-General, had died of a seizure in May, and later that month, Victor Matsu, Deputy Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, died suddenly of a virulent strain of hepatitis.

The new agency chiefs were all Vanderbilt appointees, and while each expressed eloquent grief over the demise of their seconds-in-command, the deaths somehow seemed fortuitous in light of the fact that there had been friction between the new chiefs and their career deputies, and the vacancies created by the deaths could now be filled by more agreeable people.

Almost as remarkable as the chain of deaths, was how little coverage they received. A year or two ago, such a chain of events would have kept the media mill going for weeks. Even designation of the newly promoted replacements had gotten very limited mention.

Tanner sighed, some of the tension leaving his body as resignation set in. He absently put his hand against the moisture-fogged window, feeling the cold seep into his palm. Not for the first time, he wondered where in hell Vanderbilt had come from. In one moment it seemed, he was an obscure and somewhat colloquial senator from New Hampshire, to whom no one had paid much attention. In the next, he was the most powerful public figure in the world.

The Vice President, Joseph Miller, was a former U.S. Advisor to the European Economic Council. Tall and dark, with dispassionate, questioning brown eyes that seldom blinked—eyes that seemed to bore right into your mind—Miller was another enigma. Somehow, in his quiet, dark way, Miller seemed to evoke trust. Tanner could not say why.

Vanderbilt was another matter. Tanner’s little, old-fashioned mother had a term for people like Vanderbilt. He was “vulgar,” she would have said. Vanderbilt had a habitual lewd and arrogant way in which he looked at peop

le. Not when he was in the public eye of course, but in meetings with his staff, and in private, he made no effort to disguise his contempt for others.

Oddly, for someone who was not an old-timer on the Washington scene, Vanderbilt swept aside resistance as no predecessor had ever done before. By that alone, Tanner knew that there was some heavy-duty money behind him. All the media had taken on the Vanderbilt tincture, and Washington and New York society life seemed to take on a vaguely different nuance. It seemed strained.

Tanner observed that Washington had become overt in its corruption. The rhetoric was still the same; the politicians were still “serving” their country, but the “hidden agenda” wasn’t really hidden anymore. It had become the wallpaper of Washington society. The politicians and power brokers didn’t really seem to care whether or not the public knew what they were doing. Most of them flouted their arrogant confidence that there was nothing the public could do about it. Washington had lost even the semblance of being about representative government. It was openly about power. Power and money, other people’s money, the “golden fleece” of legend.

The nation of sheep that provided the fleece might occasionally object to being sheared, and the unstated Washington objective was to apply just the right balance of threat and propaganda to keep them producing and in check. To create enough doubt and confusion to prevent open rebellion. People-handling. Manipulating the masses. It took a special talent, and Washington was a magnet for such talent. Tanner knew that it had always been that way to some degree, but suddenly it was obvious to all but the utterly blind, and supported by a ubiquitous media. All the carnivores were stepping out of the tall grass, licking their lips and openly observing the dozing flock.

Operation Damocles

Operation Damocles