- Home

- Oscar L. Fellows

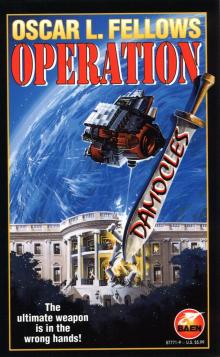

Operation Damocles Page 4

Operation Damocles Read online

Page 4

The small county fire and sheriff’s departments of Twentynine Palms were inundated by frantic callers demanding information. Half-dressed people milled in the streets, looking toward the Marine base and the rising pall of darkness that drifted on the high-altitude air currents, blotting out the stars and dimming the moon. Clusters of excited, gawking neighbors impeded authorities who were trying to reach and assess affected areas, repeatedly asking the same questions.

“Was it a plane crash?”

“Did the Marines explode a bomb?”

“I nearly bit my tongue off; I’m gonna sue somebody!”

“When will the power come back on?”

“My trailer house is tilted off its blocks, and the water pipes are broken. Everything I have will be ruined.”

Similar chaos erupted on the Marine base as bugle calls pierced the night and cursing marines hurriedly dressed for formation.

Except for a few portable units, emergency generators had to be jacked back onto concrete mounting pads before they could be started. In many cases, electrical distribution transformers and broken utility poles lay scattered along streets and highways like ninepins, and restoration of power to some areas would take days. The base and town were a pandemonium of activity as engineering and maintenance personnel in trucks and heavy equipment scattered over their respective areas of responsibility, tackling the highest priority problems first, trying to restore power and communications, and isolate broken water mains.

The flash was recorded by Defense Department Milstar satellites, NASA Observer and NOAA weather satellites over half the northern hemisphere. Seismic stations as far north as Fairbanks, Alaska, and as far west as the University of Hawaii recorded the thump of the solitary blow.

The Eidermann site had consisted of seventy or eighty abandoned buildings, mostly decaying, Quonset-type barracks, storehouses, workshops and hangars, and a cracked and weed-grown runway that was still occasionally used by Marine and National Guard personnel for “staging” exercises. The Eidermann post proper, including buildings, ammo bunkers, streets and utility works, and an old, rusting tank farm that had once stored aviation fuel, covered about ten square miles. It had lately served as an equipment storage depot for the California National Guard, and had been home to a couple of thousand pieces of moldering equipment—old “deuce-and-a-half” trucks, “water buffalo” trailers, World War II and Korean War howitzers, tanks, crates of shelter-halves, field tents and other miscellaneous gear. These items, along with the buildings, facilities, scrub brush, cactus and anything else aboveground, now comprised six thousand acres of smoldering ash.

The Marine Corps personnel and the invited city and county officials from Twentynine Palms who were picking over the area the following day, save for a few pieces of exposed underground piping, could not positively identify a single artifact. Molten metal from the armored tanks and equipment had exploded like pellets from a shotgun, to dot the area with solidified slag. Rubber, wood, cloth and paper had been vaporized without a trace. Concrete, glass and stone had exploded into fragments. The very ground itself, to a mean depth of half a meter, had exploded from the sudden thermal expansion, as the meager moisture in the desert soil flashed to steam. Clumps of shiny, vitrified sand covered the site. The result looked like the earth had been turned over by a gigantic garden tiller and scorched by flames, and all outlines of buildings and streets were gone.

###

Two days after the Eidermann incident, a Los Angeles television station came forward with a cassette tape which had been delivered the week before. They had thought the message on the tape to be from “just another nut” trying to attract attention. They received such things daily, ranging from UFO sightings and encounters with extraterrestrials to out-and-out threats of one kind or another.

The station manager had listened to the tape, and it had held his attention for a few minutes, at least until it began listing demands, whereupon he labeled it and tossed it into the junk drawer where they kept such threats and crank calls. They kept such items for a few months, just in case something happened and the police had a need for them as evidence. The mention of Twentynine Palms called the tape to the station manager’s mind, and he contacted the FBI.

The San Francisco Chronicle, Washington Post, New York Times and Chicago Tribune, among other newspapers and TV stations across the nation, now confirmed that they, too, had received copies of the tape. A few still had them. The FBI had taken possession of the Los Angeles tape, and five days after the Eidermann incident, the tape and the author of the message it contained were the subjects of an emergency congressional subcommittee hearing in Washington, D.C. On the tape was what FBI voice analysis had determined to be the voice of a middle-aged, Caucasian male. Although he sounded calm, coherent and technically educated, what he threatened to do seemed impossible for a lone man, and probably beyond most nuclear powers in the world.

The hearing, currently in progress, was being chaired by Senator William Harford, Democrat from Delaware, and extant Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. It was closed to television cameras, but a dozen journalists, and three dozen people from military and federal agencies, crowded near the front of the large, oak-paneled hearing room, leaving most of the auditorium vacant.

A wine-red carpet with a kingly black-and-gold castellated pattern covered the floor and the dais. Matching swivel chairs of rich brown leatherette lined the facing sides of polished oak tables. The tables were ornately inlaid with obsidian. A center aisle divided the rows of tables, like a small theater.

Running the length of its periphery was a long, enclosed desk that faced the room. Built-in microphones marked the desk and tables at regularly spaced intervals on the dais, and along the first two rows of tables that faced the dais from the floor.

The Vice President of the United States, Joseph Miller, occupied a chair near one wall, behind and to one side of the dais where the congressional investigators sat, and quietly observed the participants of the hearing. Secretary of Defense Harold Tanner sat on his right, with CIA Director Casper Franklin, and FBI Director Jack Mota, sitting on his left. Senator Harford was flanked on both sides by Senator Roth, Democrat from South Carolina, and Senator Isley, Republican from Idaho.

Harford, in top form this morning, was known for his ability to bluster and rail with the best of them. He was a short, heavyset man, with a round, balding, bulldog head. His face was habitually red, supported at the collar by multiple chins, and his expression was usually down-turned. His ill temper and matching scowl were focused this morning on the military contingent in the front row.

“Well, Dr. Stickle, what the hell are we up against? Does the fruitcake on this tape really represent a power that has the capability to blow up an entire friggin’ military base, or is this just a cover-up for something your screwball organization did? If the military is trying to cover up some sort of accident, the Joint Chiefs are going to regret it. What the hell kind of weapon is this supposed to be, anyway?” He waggled the cassette tape at Stickle. “We already know there isn’t any residual radiation; that’s the first thing anybody thought about. If it wasn’t a nuke, what was it? It sounds to me like somebody had chemicals or explosives stored out there. Or maybe, just maybe, one of your harebrained, experimental weapons blew up in your faces.”

Tall and thin, wearing a gray three-piece suit and wire-framed glasses, Dr. Gene Stickle looked more like an accountant than a scientist. Despite his appearance, he was one of the leading experts in strategic missile systems in the world. He was the chief physicist of the Air Force Office of Science and Technology, and currently assigned to Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado.

He sat with another scientist and two colonels from the United States Air Force Space Command, at the nearest table facing the dais and the congressional panel. Stickle was the primary target of Senator Harford’s ire today, and to his credit, he responded with calm and deliberate speech.

“The destruction at Twentynine Palms wa

s accomplished by a directed-energy weapon system in Earth orbit, Senator.”

An audible hush passed over the room. Silence reigned for a moment as the gravity of Stickles words sank in.

“You mean a laser weapon, out in space?” Harford was momentarily stunned.

“Yes. Or an advanced, particle-beam system.”

“Are you serious? How is that possible? A laser or particle beam diverges, spreads out, dissipates its energy in the atmosphere. I know that much from the Star Wars hearings I’ve sat on. It would take an energy plant the size of a mountain to produce a pulse with enough energy to start a grass fire, let alone wipe out an entire airfield.”

Harford’s bluster had momentarily gone, and he appeared genuinely confused and concerned. It seemed almost as if he were trying to reason Stickle out of some preposterous stand.

“It was not a single pulse, Senator Harford,” continued Stickle, calmly. “That’s the one thing we do know about it, and the weapon is all the more formidable because of it.

“An Air Force satellite was looking at the southern California area when the base was hit. The satellite is designed to image radiant energy in the IR—infrared—spectrum, and couldn’t image the beam itself, but it could image the impact point, or thermal bloom, as the instantaneous temperatures of things on the ground suddenly increased.”

Stickle stood up and began to pace the aisle as he talked, his left hand in his pocket, his right hand casually emphasizing his words. “The beam is a CW—continuous wave—beam, which makes us think it is a laser or laserlike form of energy. Particle beam weapons are, by nature of their power requirements, at least in our experience, pulsed energy packets. Relatively low-powered generators charge up energy storage capacitors, and the capacitors release the stored energy in a short-duration burst. This is necessary to obtain momentary energy levels in a contained plasma sufficient to create a destructive pulse. The same is true of lasers to some extent. Only low-power devices can usually operate in the CW mode. We will know more when we have the results of the material analyses that are being done.”

Stickle stopped pacing, and stared meditatively at his fingers for a moment, gathering his thoughts. The room was silent except for the hushed sounds of breathing, and the muffled stutter of weight being shifted in vinyl-covered chairseats. All faces looked expectantly at Stickle, waiting for him to proceed. He resumed pacing.

“This weapon sweeps the target area with a sharply focused beam,” he said, finally raising his eyes to meet Harford’s frowning, confused countenance. “It traces a path back and forth across the target, like a child coloring in a picture with crayons, until the target area has been covered,” Stickle illustrated a zigzag, painting motion in the air with his free hand.

“A television set or computer monitor recreates images in much the same way. An electron beam sweeps across the CRT screen from side-to-side, working its way down the screen from top to bottom in a zigzag path. It only takes a fraction of a second, about fifteen milliseconds—fifteen thousandths of a second—for the beam to traverse the screen from top to bottom, but to human senses, it appears as an instantaneous event. One doesn’t see the trace, only the completed image.

“This weapon does the same thing, and with enough precision that it could burn a picture onto the ground. As we’ve seen in the aerial slides presented earlier, the target area is sharply defined. The weapon has incredible power, perhaps forty trillion kilowatts in the beam. At least a hundred kilojoules per square centimeter at the Eidermann site.”

“How do you know all this?” asked Harford.

“By analyzing the satellite pictures, and by cursory examination of the site, Senator. The recorded satellite imagery can be slowed down, and transitory events measured against a precision oscillator, or computer clock. The satellite isn’t equipped for very high-speed recording, so we can’t actually see the trace sweep, but we can slow down the recorded signal enough to approximate a slow-motion film. In slow motion we can see the advance of the destruction as it traverses the length of the target area. It looks like the ground is erupting along a moving, parallel front. It took approximately half a second to traverse five miles. To those in the area, it seemed like just one colossal explosion.”

Stickle motioned to his fellow scientist, who began taking papers from a briefcase. Stickle returned to his seat, but remained standing, taking various papers as his colleague handed them to him. He continued speaking as he shuffled through the documents.

“Metals, such as the steel of the armored vehicles and the aluminum in the electrical power lines that cross the area, have specific melting temperatures, vaporization energies, et cetera.”

He studied a paper briefly, then read an excerpt from the report. “The metallic aluminum from the power lines was found in a condition of melted slag, with approximately thirty percent of the expected mass missing.” He looked at Harford briefly.

“Vaporized, in other words. Based on the estimated beam diameter and sweep rate, any given object was in the beam for a period of about two microseconds—millionths of a second. The duration of exposure and the enthalpic energy necessary to vaporize the missing aluminum, along with other factors, gives us an approximation of the energy in the beam.

“Regarding the frequency of the energy beam, the penetration of the earth and the anomalous magnetic fields in some of the affected materials give us a few clues, also. The Marines who reached the site almost immediately after the blast reported burning throats and eyes from high concentrations of ozone, meaning the air was strongly ionized to the point that high-voltage, high-amperage electric currents had flowed through it. Given all that, we believe the beam is in the X-ray, or hard ultraviolet portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.”

“How could they accomplish such a weapon system when we couldn’t do it?” Harford demanded. “We spent billions on research. If it’s feasible, why don’t we have the damn thing?”

“We don’t have it, Senator, because you, among others, cut the funding for the research, even before the breakup of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. Even worse, what funds were put into directed-energy weapons research were mostly given to favored defense contractors with heavy political clout, rather than to innovative companies that might have solved some of the problems. Space sciences and defensive weapons systems have all suffered tremendous cutbacks since 1988.”

“I’ll ignore your insolence, Doctor. The important question now is, can you defend against it?”

“Possibly, in time.”

Harford persisted. “Can you shield buildings from it . . . erect some sort of heat shield?”

“We don’t yet know the specific frequency of the beam, Senator, or its exact makeup, but laser energy can be defeated by reflective and ablative coatings. Reflective coatings act to reflect the energy away, as a mirror reflects sunlight. Ablative coatings are surface films which absorb the energy of the beam and flash into vapor, thus dissipating the energy and leaving the coated object intact.

“Trouble is, we don’t know how much control they have of the weapon. They can potentially sweep the target area repeatedly, several times per second. Ablative coatings would be gone after the first sweep. Reflective surfaces require highly precise coating techniques, especially in the higher-frequency end of the spectrum; it’s not simply a paint job. At X-ray and hard UV frequencies, some solid objects are transparent, which further baffles everyone about the Eidermann site. Many of the objects at the depot should not have absorbed the energy of the beam at those frequencies, yet they did.”

Stickle regarded Senator Harford, his look indecipherable. “Even if a protective coating was simply a matter of applying a coat of paint, how do you propose to paint every city in America? We could conceivably minimize the damage to some things by using conventional site-hardening techniques, such as covering exposed sites with rammed earth or foamed concrete, but we don’t have the time. Assuming they keep their word, and use the weapon again within thirty days of th

e Eidermann warning shot, the deadline is now only twenty-five days away. Even if we had enough deep basements and caves, how could we possibly get several million people into them, and equip and provision them, in three weeks’ time? Who would dig them out afterward? If these people have the power they claim, then they have the power to do any damned thing they want, and the government has no option but to give them whatever they demand.”

“I can’t accept that,” said Harford, his assurance returning. “You said that in time, it might be possible to defend against it. What did you mean?”

“I mean that we need time to learn. We have no information to work with yet. Neither the Defense Department nor NASA can locate the weapon. We’ve been searching for it with everything we’ve got, for the past five days. We’ve found nothing. It possesses advanced, stealth, cloaking technology. We don’t know how it works, what its fuel and energy limits are, how it is controlled, or where it is controlled from.

“If it has finite resources—for example, if its power plant is chemically fueled—it could literally run out of gas. It may already be out of fuel. For all we know, it could be a one-shot device designed to throw a scare into the United States government. We don’t believe that’s the case though.

“We’ve found no trace of an energy-emissions signature in space—a cloud of hydrocarbon gas such as a chemically fueled generator would produce. If it does have extended operating capability, such as a nuclear power supply, then our defensive best bet is to identify the control signals, and either interfere with them or take control of the weapon ourselves, and neutralize it in that way. If we can locate it, it may be possible to destroy it with a missile.

“In the meantime, we need to negotiate, to buy some time. If we knew who we are dealing with, it would help. It could be a terrorist organization in the Middle East . . . maybe even an old-guard Soviet or Red Chinese splinter faction that hasn’t yet given up the idea of destroying us in a decisive global engagement. Whoever they are, they have access to state-of-the-art military technology, and the funds to acquire it. They also have the technical know-how to use it. If we knew who they are, we would at least know something about their motivations.

Operation Damocles

Operation Damocles