- Home

- Oscar L. Fellows

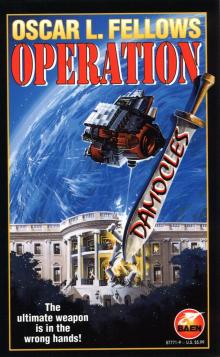

Operation Damocles Page 8

Operation Damocles Read online

Page 8

Barely five feet seven, Broderick carried a big chip on his shoulder. Unsmiling and hard-eyed, he was never sociable and never made small talk. Few people outside those in mail distribution even knew his name, save for his secretary and perhaps a few in the other sections in the immediate vicinity of his office. He came and went with little notice. The people he passed in the hall really had no idea of what he did. When he did talk, it was to one of his staff or his immediate superior, and it was curt, to the point, and never friendly.

A certain faction in the CIA community had recruited Broderick three years earlier, in an under-the-table fashion, from the Cosa Nostra. The agency had need of his intimate knowledge of the underworld, and all his useful connections. It just so happened that it was also a good deal, and good timing, for Broderick. He knew a little too much about his former “family,” and a few of his “relatives” were at the point of “punching his ticket” when the agency brought him inside. He was intelligent and ruthless. In short, he was as ugly a piece of work as ever came out of Brooklyn, and he was well suited for what he did.

Broderick was a domestic “mole,” an underground operative with broad latitude and a hidden budget, secret even within the intelligence community. Like the few others of his kind, he served the hidden leadership of the nation, the underground power structure that really dictates federal policy—the anonymous money and power that makes and breaks politicians and industries.

Even he did not know who the ultimate powers were, but he knew they had vast resources, and he knew they manipulated governments as the hidden puppeteer manipulates wooden dolls. The public had no knowledge of this conspiracy that starts and stops wars, and controls world resources and markets.

Broderick and his kind were secret from the public because what they did was illegal; it was outside the scope and authority of the CIA charter and every other legal tenet. The CIA wasn’t supposed to meddle in the internal affairs of the United States, and indeed, only a very few within the agency were aware of internal, isolated groups like Broderick’s. His orders originated outside normal agency channels, from the White House itself, and sometimes even closer to the elusive aura of power that controlled everything.

On the morning of July 26, Broderick opened his office door to admit one of his operatives. James Reed was an experienced field agent, a communications expert, and had only recently become a member of Broderick’s very exclusive staff. At six-two, Reed stood head and shoulders above Broderick, had a broad-shouldered, athletic build, and as with all bigger men, Broderick had disliked him from the moment they had met.

Reed had been screened for Broderick’s team because he had worked as a foreign operative for the National Security Agency in the Middle East during the Iran/Contra days, and had been someone “in the know.” He had been loyal and reliable, and had worked hard to mitigate the damage to the NSA. He had helped to cover the agency’s tracks by destroying incriminating evidence and sending congressional investigators down blind alleys. He had also performed a few damage-control missions in the past, missions that required more than normal discretion. He was considered a “good soldier.”

A farm boy from Kansas, Reed had been inducted into the community during his fourth year in the Marines. He was twenty-one when he became an agent, and after seventeen years, the agency was his home. He was loyal to it—believed in it.

Broderick didn’t respect Reed, or anyone else for that matter, regardless of their loyalty, ethics or dependability. He considered people to be no more than tools, and he treated his tools with disdain.

Without inviting Reed to sit, he asked: “What about this TV news broad, Reed, the one in Indiana? Why couldn’t we kill the broadcast over the networks? Those satellite-communications geeks in Central Communications Services are supposed to see that crap like that gets filtered out. The international wire services picked it up.”

Reed walked into the office casually and, turning, faced Broderick as the smaller man closed the door and walked back to his desk. “They have a satellite link with an unlisted translator frequency,” Reed replied calmly to Broderick. “No one knew it until CCS tried to kill the signal during the downlink delay. Even the TV station thought the frequency was registered. They have an approved frequency assignment. It was just a paperwork foul-up. We can’t cover every little, podunk TV and radio station in America without ever missing a single detail somewhere.”

“What about the opinionated broad?”

“Her name is Beverly Watkins. We got her fired. She won’t work in broadcasting again.”

Broderick turned livid. “You brainless fool,” he flared. “Do you have any idea what you’ve done? You don’t get them fired. At least not right away, and not over the real issue.”

He sighed, shook his head, and explained as if to a child, ticking off each point on his fingers. “Get with the program, Reed. You have their management people counsel them against using antigovernment rhetoric. If they don’t straighten up, you have their management fire them over job performance issues, such as being habitually late for work, or having a drinking problem, or even over artistic temperament. Those things will effectively blacklist them within the industry.

“If they actually have any suspicions that they are being isolated from the public, and get vocal about it, you have the IRS apply pressure to their families, their adult children if they have any, or their friends. It’s more effective that way than applying pressure directly to them. They can feel self-sacrificing, instead of ashamed, for not retaliating.

“You shut them up, Reed, you don’t give them ammunition and motive to use it. Because of your bungling, she’ll file a suit, as sure as I’m standing here. Suits like that attract citizen watchdog groups like a carcass attracts flies. It makes a mess, Reed. Important people have to answer questions. My question to you is, how are you going to clean this mess up?”

“I don’t understand why it was necessary to shut her up in the first place,” Reed responded calmly. “It’s not as if she were on a crusade against the government. It was an isolated incident, and with all the other media circuses this thing is producing, it would have faded from public consciousness within a few days. Even if a few people took notice, what does the opinion of one ordinary person matter?”

“Why is not your worry, Reed. She’s not an ordinary person. She’s a public figure. A newscaster . . . even if a minor one. We can’t have wild-card revolutionaries in the communications industry, if we are going to keep order. As long as they are not directly challenged, Americans will grumble and complain, but they will remain passive. We can’t have someone in the media stirring them up. It would be an authoritative voice confirming their deepest suspicions. Because of your bungling, we’re going to have to find a way to silence her.”

Reed looked at Broderick as if he had just turned over a rock and found something disgusting. Broderick glanced at Reed, noted the look, and glared back at him, black eyes filled with hate.

“What made you pick me for this outfit, Broderick?” Reed asked. “I’ve done things for God and country that would turn even your stomach, and I haven’t questioned much, even when I felt like scum for doing it. I took it for granted that wiser heads than mine had weighed the need, understood the gravity of what we were doing, and had decided that no matter how terrible it was, it was necessary and justified. Now, you’re talking about doing it to American citizens. I can’t see how that can be called protecting America. Not by any stretch of the imagination. It’s not even legal, according to our charter. Does your chain of command approve of what you’re doing, Broderick?”

Broderick stood, keeping the desk between himself and Reed. “You have your orders, Reed. Clean up the Watkins thing. You’ll do whatever I order you to do, or you’ll become a GS-3 orderly at the Pentagon. You will get increasingly poor performance ratings for the next six months, and then you’ll be fired. With that in your Official Personnel File, you couldn’t get hired to clean restrooms in a national park. You’ll los

e your pension, and you’ll be blacklisted everywhere.”

Reed looked at Broderick for a long moment, as if absorbing a new idea. Finally, “What do you want me to do?”

Broderick studied Reed’s face. “I think you had better arrange an accident,” he said. “Maybe she surprises a burglar, and he panics and kills her. It’s the only thing we can do, now. We don’t have complete control of the municipal courts. If we wait till she files suit, she’ll be in the public eye. If we try to talk her out of it, she’ll know for a fact that something shady is going on. We can’t afford any more public suspicions that the media is being controlled. Not for a few more months, at least. You have the resources and the people, Reed. Make it happen, and don’t screw it up.”

“You’re insane, Broderick,” Reed said quietly. “You have no reason to kill her. There are many ways to discredit her. She’s an American citizen, and she’s not really a threat to anyone in government, or to the security of this nation.”

Broderick stood, tense, eyes glittering with inner hate. “We’re going to make an example of her, Reed, to the industry. If we don’t punish her, radicals in the networks will get bolder. If the networks start letting rebel newscasters be heard by the public, they will raise issues we don’t want raised. The news media has to be kept in line . . . and so do you, Reed.

“This isn’t the Cold War—us against a foreign enemy. This is the beginning of the new world order. National boundaries don’t exist anymore. Business and politics are global. If you can’t adjust your thinking . . . if you insist on acting like a patriotic fool . . . you will regret it. I can promise you that.”

The two men stared at each other, each a ruthless killer in his own right, but with a difference in philosophy that was miles apart.

“Are you going to do your job, Reed?” Broderick asked directly, outwardly calm.

“I’ll have to think about that,” Reed said. He looked at Broderick, as if speculating, then turned on his heel and left, closing the door behind him.

After a moment of thought, Broderick picked up the phone and dialed. He stared at the door through which Reed had just left, and after a brief wait, said into the phone, “I think we’ve got a problem.”

XI

The congressional debate started on July 29, and raged for six days. The western politicians were willing to adopt a wait-and-see posture, while some of those from the east had constituents who were understandably frantic for someone to do something. No further word was forthcoming from the people wielding the space weapon. Television talk shows were counting down the hours until the threatened calamity—milking viewer fear to increase audience share.

The repeated assurances of government leaders had swayed the majority of citizens in the designated disaster zone and most were staying put, but no amount of assurances and scoffing could allay the fears of everyone, and some were leaving, taking household effects and all. The two-lane roads throughout much of the rural northeast were choked with overburdened cars and U-Haul trailers, kids and pets hanging out the windows, the roofs bending under the weight of furniture and appliances.

The fact that public officials from the “zone” suddenly seemed as rare as winter corn helped to convince the more astute that this wasn’t just a drill. Some reasoned, and justifiably so, that if even the con men were leaving, then the threat might not really be just a terrorist bluff, as Washington insisted.

If it takes one to know one, it was understandable that many in Congress and state government had learned not to put too much faith in anything that came out of the Vanderbilt White House. As the deadline drew near, many of the politicians and the well-to-do were finding it a good time to vacation, or take a business trip to Europe, Hawaii or points west, with the family. The President and most of his cabinet just happened to be out of town on various and sundry missions before the scheduled date arrived.

Congressman Harford put on a defiant show, stating that he would not alter his schedule in the least, and would laugh at the “yellow-bellied reactionaries” among his colleagues after the thing had blown over.

Sporadic fights erupted in a few communities as angry citizens tried, some successfully, to evict stubborn civil officeholders from their nests. Some citizens and a few law-enforcement personnel were killed or wounded. National Guard units, and strategic and tactical military bases were on alert everywhere. Some states had called up National Guardsmen to protect government offices from rioters.

Many of the smaller cities and towns in the rural areas tried to comply with the conditions set forth in the taped message, at least as far as setting up adult education curriculums in their schools, striking victimless crimes off the books, and adjusting their payrolls and administrative budgets. Small-town politicians and civil servants tended to be closer to the people they served, and did not put up the arrogant resistance to eviction that their career brethren in the larger cities did.

Within the federal government, the executive and judicial branches refused to consider meeting any demands whatsoever. Congressional committees debated endlessly, and every representative that took the floor offered some provisional willingness to “look into” some of the terrorists’ stipulations, which “might be possible if substantially amended.”

Government agencies downplayed the warning, following the administration’s lead, trying to get the public back into a calm and tractable state of mind. The official word was that if anything did happen, and that was considered doubtful, the military, the FBI and the other federal authorities were ready for it and would make short work of the terrorists. None of the demanded actions were taken at the federal level, and the few small-town attempts to comply were not consequential enough to merit serious media coverage. All in all, it was a wash. Unknown to the public, terrestrial and orbital eyes were scanning the heavens incessantly, looking for any clue to the location of the weapon that the President had all but denied existed.

###

On August 6, five days before the threatened destruction, at 2:15 a.m., a tremor ran up the length of the east coast of North America like a giant, rumbling freight train passing in the night. The jarring vibrations were accompanied by staccato claps of thunder that wakened sleeping neighborhoods and knocked out power in isolated utility substations at approximately twenty-mile intervals, from Washington to Maine.

That evening, the news reported that an overload had caused power outages up and down the east coast, and that power grids were rerouting trunk lines as quickly as possible. Local news stations warned that further short interruptions might occur as workers made repairs. Utility company public-relations people and police went door-to-door in the affected areas, distributing hurricane lanterns and explaining that residents should buy ice and Styrofoam coolers to preserve perishable foods, because the power might be off for another twenty-four hours or so.

No one told the public that all the electrical substations affected had been reduced to smoking slag. No one mentioned the taped message that expressed one last plea, and a final warning. The Vanderbilt administration had decided to take direct control of the dissemination of information to the public, and by doing so, draw the fang from the terrorist’s mouth.

###

Harold Tanner sat at a breakfast table in the presidential suite with President Vanderbilt and Vice President Miller. Vanderbilt was eating breakfast while the others drank coffee. It was the morning of August 8.

“They knocked out twenty-two electrical distribution stations,” Tanner was saying, “along an almost straight line from Washington to Boston. Nobody hurt that we know of. The stations were mostly minor residential distribution points that could be easily rerouted. Nothing was hit that would seriously impact anything; no hospitals were deprived of critical power—nothing major at all.”

Vanderbilt smiled. “And why do you think that is, Harold?” he asked, his eyes crinkling in merriment as he cut his eggs.

“Obviously, they didn’t want to hurt anyone,” he said, “but they did demon

strate that they have the capability to fire again, Mr. President. In light of this, I think we had better assume they can do what they say.”

“You’re missing the most obvious point, Harold,” Vanderbilt said while spreading lemon marmalade on toasted English muffins. “They demonstrated two things. They demonstrated that they can fire, and they also showed me that they haven’t got the guts to make good on their threat.

“If they wanted to really throw a scare into the government, they would have obliterated Washington, or Hackensack, or Newport News. We’ve got the idealistic bastards by the short hairs, now. Ha! Mark my words, on the eleventh, those simpering, gutless patriots will chew up some more unoccupied turf somewhere, if they do anything at all, then their bluff will fizzle. It’s a standoff, Harold, and we’re holding all the cards worth having. A weapon is worthless if you haven’t got the balls to use it.”

“I take it you’re going to stay here and defy them,” said Tanner.

“Not on your tintype,” said Vanderbilt. “The one target they might hit, if they can work up the gumption, is the capitol.”

“What about warning the public?” Tanner asked.

Vanderbilt paused with a strip of bacon halfway to his mouth and looked hard at Tanner. “Don’t be a damned fool. What have I been saying, Tanner? If you start a panic, they’ve won. We can’t encourage them. As long as we ignore them, they’re impotent. The presence of the public is what insures that they won’t fire on a city.”

Vanderbilt resumed his ministrations with his food and said, more calmly, “No! They’ve just about run out of gas, both literally and figuratively,” he chuckled. “Now, if you will excuse me . . . Oh, on your way out, tell Dahner to come in. I’m going to leave for Palm Beach this evening. You boys can do as you like. Just no public leaks. I’ll be back on the fifteenth.”

Operation Damocles

Operation Damocles