- Home

- Oscar L. Fellows

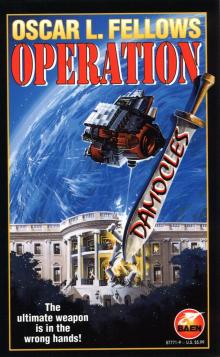

Operation Damocles Page 15

Operation Damocles Read online

Page 15

It was not only the United States that had changed. The rest of the world had paused also, waiting and wondering. Though they had not yet suffered directly, they seemed to act in unspoken unison, suspending regional hostilities and general saber rattling. It was almost like a noisy cocktail party that suddenly falls silent, and stands attentive and waiting when the police walk in.

He sighed. He was tired of months of useless speculation, and he just wished he could disengage from it all. He would have liked to sit it out on the sidelines, and simply wait and see what the foolishness of his fellow men would bring. He wondered why he didn’t do that. Quit and go home. Probably because there were no “sidelines” anymore, he thought. The nationalists had seen to that; everyone was involved whether they liked it or not.

He didn’t presume to know what was right anymore. He really didn’t think that anything was. People were just out for themselves, and what was “right” depended on where you stood. Shakespeare had defined existence best: the world is just a stage where people play out their individual parts.

“And,” Isley added out loud, “when we disappear and are forgotten, the universe won’t really give a damn.”

XX

It was Christmas Eve in Menlo Park, California, and Jack and Eve Townsend—formerly James Reed and Beverly Watkins—were smiling at each other across a dinner table in the Steak Ranch restaurant. The remains of turkey and dressing dinners had been removed by the waiter, leaving a partial bottle of wine, their glasses, half a loaf of brown bread and a large wedge of Baby Swiss cheese.

Jack had taken a position as a project manager for an engineering firm which was located just down the road in Mountain View. Prouss Engineering did contract work for the NASA-Ames Advanced Projects Laboratory, near Sunnyvale, as well as other, private-sector contracting.

The job had been arranged by an old friend named Edward Teller, who had retired from the “Community” several years before, and now lived in Santa Cruz.

Teller had also arranged for Townsend to meet a physics professor named Ortiz at Stanford University. Dr. Ortiz was head of the Coherent Radiation and Optical Science Department in the College of Electrical Engineering. Townsend had spoken to him earlier today, by phone. Their first meeting was to take place the day after Christmas.

Jack and Eve had returned from Las Vegas, Nevada, earlier in the day, where they had been married. Eating, sleeping and spending every waking moment together for three and a half months, they had endured what seemed an eternity of fear and privation.

During those long, fear-filled weeks, they had also developed the suspicious care and acute senses of the hunted, and become solely dependent upon each other. They were now a working team, almost reading each other’s thoughts, anticipating the other’s next action instinctively, before it took place.

They avoided the police as a matter of course, going out of their way to avoid potential encounters. The risk of being recognized was low, but the safest risk was the one not taken, and while the tension was less now, Townsend would not allow them to become unobservant and lax in their precautions. It had gotten so that they derived comfort only from each other, and were fidgety and fretful when they were apart.

Fear has a way of building a bond of loyalty and absolute trust in people dependent upon one another for survival. For Jack and Eve Townsend, that bond had developed into tempestuous love. The last ten weeks had been a time of small miracles, due principally to Edward Teller. Teller had taken them in from the cold, and helped them to be reborn into a new life. He had rented a house for them in a secluded canyon a few miles from town, bought them a car, and now, gotten Townsend a job.

Teller was retired from the federal government, but kept his hand in by applying his knowledge of federal procurement. He worked intermittently as a freelance consultant to small companies and universities that did business with the government. He had worked closely with many small, high-tech businesses, and knew a number of their managers and CEOs very well.

For Eve, haunting memories and fears still lingered, and no doubt, would continue for some time. Eventually, they would fade. At the moment she was relatively happy—in a Christmas-time, melancholy kind of way.

Two weeks after they had arrived in California, she and Jack had come home to their new house from a late dinner at a restaurant. They were still sleeping in separate rooms, and up until that night, nothing of an intimate, romantic nature had passed between them since that memorable night in Miami, seemingly so long ago. Their relationship had changed, though. They were friends and allies now, beyond any reason or necessity, and they confided everything to each other. They felt totally at ease and secure with each other.

That evening, they were sitting together on a redwood glider that, aside from a small table of like construction, was the sole piece of furniture on a railed, wooden verandah that overlooked the rocky, cedar-covered canyon in back of the house. They sat in partial darkness, enjoying their after-dinner coffee and talking.

The late evening air was slightly damp and chilly, but not uncomfortable, and bore the faint fragrance of cedar, pine trees and juniper. The canyon was a dark well, falling away beneath the verandah, and the hill on the other side of the canyon was a black outline against the starry sky.

Eve had been job-hunting during the days, as had Townsend, and they had just been discussing the poor pickings so far. She had been feeling more resigned than depressed, at that point. Unexpectedly, he reached out and turned her chin toward him, and leaning over, he kissed her very gently on the mouth.

“Will you marry me, Bev?” he asked.

As close as they had become, she hadn’t seen it coming. She knew that she loved him. She had hoped that he would stop being the methodical planner and the perfect gentleman someday soon, and begin treating her as a desirable woman, but so far, he had been exasperatingly noble and patient with her.

When he finally spoke, though, her mind was on all the endless job applications she had filled out during the past weeks, and she was just about to tell him that she wished they would pass a law making everybody in the world use the same employment application, so she could just hand in photocopies, when he caught her totally off-guard. She looked at him blankly for a moment, while it registered.

Thinking he understood her hesitation, Townsend tried to explain, in the logical, patient fashion that she had come to know.

“I know this is out of the blue,” he said, “but you must have thought about us, too. I don’t know when I actually started thinking about us staying together. I guess it was that night back in Miami. Now, I can’t imagine leaving you somewhere, and never seeing you again. I don’t even want to imagine it. I don’t think I could do it, even if you wanted it that way. I don’t want a life without you in it.

“You were married, and you had a life and a home with someone else. I never have. I’ve never loved anyone before. Honey, I’ll wait as long as it takes, until you can begin to love again. I’ll take care of you—make a life for us. Will you marry me?”

She smiled, and tears filled her eyes as she kissed him back, and she put her arms around his neck, drawing him close.

“I was beginning to think that you were never going to ask me,” she said. “Lately, I’ve considered jumping you in the middle of the night, but I was afraid you would shoot me before you knew who it was.”

“No danger of that,” he grinned. “I’ve lain awake at night thinking about you, oh, for the last three months or so.”

That was the first night they had slept together. Since that night, she had endured a strange mixture of bliss, melancholy and concern for the future.

Now sitting here together, married, and for the moment perfectly content, it was beginning to look like they had found a home and happiness together. Tomorrow they would spend Christmas Day with Edward Teller and some of his friends.

“It doesn’t seem possible that only a few months ago we lived totally different lives—really lived in a different world,” said Ev

e. “All that seems so very long ago. The craziest part of it all is that I’m beginning to get used to life being an unending, immediate crisis.” She toyed with his collar, and put her hand on his face. “I think that you and Nathaniel would have liked each other. Do you think I can go back and visit his grave, someday? Just to say good-bye?”

Jack smiled sadly, and took her hand in his. “Of course, honey, in a year or so. It will take awhile for that connection to grow cold. In the meantime, I want you to do me a favor.”

“What is it?”

“You called me Jim twice yesterday, and you have to put those names out of your mind. That’s not us anymore. A trick I learned in the espionage business is to make your cover identity a fact in your own mind. I’ve had to assume a role on short notice, and I’ve learned the only way to avoid mistakes, such as inadvertent slips of the tongue, is to convince yourself that you are your new identity. That old identity was just a role that you played for a while, and now it’s over.

“It really works,” he responded to the beginning, small shake of her head. “You have to use my new name in your thoughts. Really think of me as Jack Townsend. In a few days you will fool your psyche into accepting it, and it will eventually become natural. You have to do the same with your own name, too. It’s a serious concern for us, baby. The first time you run into someone you’ve met at a function, and reintroduce yourself as Beverly, and they look at you strangely and say, ‘But I thought your name was Eve,’ you will realize that you’ve made a mistake, and it’s going to be difficult to make someone forget an incident like that. They will tell their friends. Pretty soon you’re ducking invitations and staying indoors, and the more suspicious you act, the more suspicious people become.

“I’ve learned that it doesn’t make a whit of difference to your cover whether you live as a lion or a mouse, as long as the cover is solid. People are only suspicious of someone whom they think they don’t know enough about. If you are a loud-mouthed, blustering boor, or a sad little wretch, you will be accepted, but if you are the least bit mysterious, they get really curious. People love scandal, large or small, as long as they are not the focus of it.

“To avoid that kind of situation, we must play our roles to the hilt. Play it until we become the role. Believe me, honey, you can do it.

“Tell you what, say a sentence with my name in it ten times. Say it with your eyes closed, and while you’re saying it, picture me doing whatever you’re saying.”

“Oh, Ji . . . oh, I’ll feel silly.”

“Please.”

She mustered herself, closed her eyes. “Okay,” she said, smiling self-consciously, “here goes. Jack be nimble, Jack be quick, Jack jumped over the candlestick . . .” She stopped, clamped her teeth together, opened her eyes wide a couple of times, then started laughing silently, shaking with mirth.

“What is it?” he asked, smiling in sympathy with her, his brow creasing in curiosity, and just a little worry for her.

She snuffled, blinked at him, red-faced with the effort of trying to contain herself. “Jack burned his balls,” she whispered hoarsely, and broke down, laughing out loud. She tried desperately to curb herself, but broke down again. Tears of laughter ran down her cheeks.

The nearest other patron, a man sitting three tables away, grinned at Jack and looked away. He couldn’t have heard what Eve said, but he responded naturally to her fit of laughter.

Jack realized that he had never seen her laugh before. Emotion welled up in his throat, constricting it painfully, and his eyes filled, too. He knew then, just how much he had come to love her, and suddenly, how happy she made him. His life had been so methodical, so stripped of emotion, that happiness was something new, something long forgotten. Now, she was his life.

He recovered himself, blew his nose, sat there with a twisted grin on his face as he waited for her to subside. She did for a moment, gathering herself, catching her breath. Then she looked at him and broke down again, her head on the table, holding her hurting stomach.

“I’m shocked, madam, truly shocked at your loose behavior,” he said in his best imitation of Cary Grant. “I thought that you were a respectable woman. Now I find that you’re just another little tart. Burned my balls, indeed!” He laughed.

She looked at him, tears streaming down her face, clutching her napkin to her mouth. “I pictured you jumping a flaming candelabra, just like you said. You had a sign around your neck with Jack written on it, and you were naked,” she sobbed. “It just came into my mind . . .” And she broke down again, in spasms of laughter. This time, he joined in. The sparse clientele in the restaurant looked at them momentarily, then turned back to what they were doing, as if they assumed that the laughing couple were slightly off-kilter, but harmless.

XXI

Hector Ortiz was short, in his early sixties, had white hair with a small bald spot at the back of his head. He was a native Californian. He wore plastic-framed glasses with bifocals. He was habitually in a white lab coat when at work, and his colleagues thought he looked strange when they saw him in other clothes. He was outgoing and playful by nature, but outwardly sarcastic. You had to get to know him to realize that he wasn’t the grouchy old curmudgeon that he pretended to be.

Despite the lab coat and the credential, Ortiz was more of an administrator than a scientist. He knew a lot of people throughout academia, and he could get things done. He obtained grants prolifically, and while he generally kept his secretary and the accounting department pulling their hair out by the way he applied appropriated funds in a helter-skelter fashion, he was generally well-liked, and kept harmony in his department.

He published one or two short, innocuous papers a year. He was also comfortably installed in a somewhat arcane niche and wasn’t jousting with anyone for higher position. He had tenure, and he had one other outstanding quality; he thumbed his nose at bureaucratic authority. He also had a Hispanic friend on the Board of Regents, and because of the Boards unofficial emphasis on minority tenure, anyone would’ve had a hell of a time in ousting him.

It had worked well throughout the better part of two decades. No one had ever bothered trying. His resulting sang froid bothered a few of his superiors, but not sufficiently to spark any real enmity. In short, he was pretty much bullet-proof, and he knew it.

His meeting with Jack Townsend was at the request of a mutual friend, a C.I.A. friend who had gotten him out of Cuba when the Batista government fell.

He had been a visiting graduate intern at the university there in 1959, when the proverbial excrement hit the fan. He had spent three days running and hiding, while fellow academics were rounded up. Those that were Cuban natives with families couldn’t avoid capture—there was too much leverage over them. It had not gone as harshly with them as they had feared, but at the time everyone was in a panic of terror, thinking they were to be shot or imprisoned, and afraid for their families.

When he had stumbled into the big C.I.A. agent, he had never been so glad to see an Anglo face in his life. It was American, and he hoped, friendly. It turned out far better than he had hoped. The man was from the same area in California, and four hours later, Ortiz was with him on a small seaplane, bound for Miami.

Memories of those days were also a part of his personal armor. He had never been that afraid again. He and his savior, Edward Teller, had become close friends during the following years, and Ortiz had been involved in a number of C.I.A. community science projects. Both were bachelors, and after Teller retired, they became regular companions, fishing together on weekends, or watching sports on TV.

Ortiz was generally open to visitors and would have met with Townsend anyway, or almost anyone else for that matter, but Teller had introduced Townsend by phone and explained the special nature of this visit. Ortiz was very curious to meet the man. When he did meet him, in his office, on the afternoon of December 26, he suddenly remembered a forgotten feeling, a presence that he hadn’t experienced in a long while. He already knew what the man was. His friend

had told him, but he would have known anyway. He knew that look, that subliminal cast of the features, and his curiosity grew.

Before Townsend could speak, he advanced, shook hands and said, “I’ve been around enough spooks to know one when I see one, Mr. Townsend. I see Dr. Philips, the scientist in charge of your Community Affairs Office, once or twice a year at the odd convention or seminar. Know him?”

Townsend smiled guardedly, “Dr. Robert Emerson has been in charge of the Community Affairs Office for the past two years, Dr. Ortiz. Eddie said you were an ‘irreverent old spic,’ but he didn’t tell me you were tricky, too.”

“Did he call me that? Did that old, honky asshole call me a spic?” He pretended great offense. “What else did he say about me?”

“Just that he wouldn’t trade you for all the oil in Alaska. I take it that you two have some sort of history together. Eddie didn’t elaborate except to mention that he met you in Cuba during Castro’s revolt. At any rate, he thinks a lot of you, and I trust him, so here we are.”

Ortiz laughed. “Eddie and I go back to just about the fall of the Roman empire. We’re keeping each other company while everything is slowly being overwhelmed by the Brave, New World. Or to put it crudely, we’re watching everything go to hell in a handcart. What would a pair of old farts like us do, without someone our own age to commiserate with? You young dipsticks don’t remember when cigarettes were a quarter, or when a hamburger or a gallon of gas was thirty-five cents. You’ve probably never even seen a drive-in movie.

“In my day, you could take your girl out for a hamburger and a beer, and go to a double feature with cartoons for five bucks. It was a magic age. A different way of thinking that no one can describe. Do you remember the Ventures? ‘Walk Don’t Run,’ ‘Pipeline,’ ‘Perfidy’? Or Roy Orbison, ‘Pretty Woman,’ ‘Crying,’ ‘Blue Bayou’? Or ‘La Bamba,’ or Harry Belafonte, ‘Banana Boat’? How about Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, or Peter, Paul and Mary?”

Operation Damocles

Operation Damocles