- Home

- Oscar L. Fellows

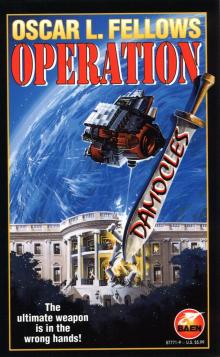

Operation Damocles Page 16

Operation Damocles Read online

Page 16

“I vaguely remember a few of those. I remember the Beatles.”

“The Beatles sucked. They, and that whole tribe of gangly legged, long-haired British hippies, ruined American music.”

“I didn’t say I liked them.”

Ortiz considered him for a moment. They both laughed.

“I can see why you and Eddie get along,” Townsend laughed. “You’re a pair of crotchety old bastards.”

“Well, it beats being pubescent young assholes,” Ortiz said, sitting down at his desk, and gesturing Townsend toward a chair. “What’s going on in Spooksville, anyway?”

Townsend sobered, watching Ortiz’s face narrowly. ‘This is not a company matter,” he said, “and I wouldn’t want it to get to them. There is some risk in associating with me. If that worries you, we’ll end it there. I’m not about to get a friend involved unknowingly, or the friend of a friend. I need some scientific help, and Eddie seems to think that you can supply it.”

Ortiz waved his hand dismissively. “Eddie told me all that. What is it you want?”

“I’m trying to find the people who made the weapon. I need someone who knows his way around in the physics community, someone who is familiar with what has been published and what hasn’t, someone who’s tied into the worldwide physics grapevine. It’s inconceivable that something like that could be built, and nobody know anything about it, or how it was done. If I knew what kinds of parts were involved, I could trace parts and materials shipments.

“Somebody knows who they are, and more than a few somebodies suspect; but amazingly, no one in the physics community, outside the government anyway, is even making a guess. Why is that?”

It was Ortiz’s turn to scrutinize Townsend. “Why do you want to find them?”

“I think I want to join them. Corny as it sounds, I want to fight for the rebirth of democracy in this country. I’ve been a part of the other side, and I know firsthand what this country is up against. I want to salvage humanity while it’s still possible, and I don’t believe there will ever be another opportunity like this one. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime chance. We just can’t let it slip by. If that weapon system fails, for whatever reason, we will have lost our only hope. They are too entrenched—too well established for us to gain control by any other means.”

“Things seem to be pretty well in hand, in that respect. What makes you think that you can help?” asked Ortiz.

“I have the know-how to find the maggots buried under the flesh of this country. I know how the network is set up, and I know at least one individual who can get me started down the trail. I have personal reasons, too.

“If I have to operate alone, I will, but that way is too slow. I need help. That weapon gives humanity a fighting chance. We have to loll the puppet masters now, or we will never win this nation back. Those people are still with us, and they are not going to give up. If that weapon goes away, they will be back, big time.”

“Could you identify and locate all these underworld kingpins?”

“I think so, but it would be much faster with help. I could ferret a few of them out, I’m sure, but this underground is worldwide. These people are part of the international set. They move around this nation and from country to country the way you walk across this campus. They live everywhere, but mostly on the coasts. New York and California are home to a lot of them—or New York was, before that weapon fired. They’re in all the jet-set capitals of the world—Paris, London, Rio. It’s going to take a lot of digging to find all the corporate connections, affiliations, history of buy-outs and mergers—almost like tracing family trees—and I haven’t the resources to get very far alone. It’s just too big a job for one man.

“It’s one thing to suspect someone, but it’s another to find the proof. I need the help of some dedicated researchers, and I no longer have a huge government budget with which to hire them. I need people who can manipulate computers, get into banking records and trace company pedigrees. Where the nationalists are concerned, I need specific information about the kinds of parts that would be required for such a weapon, so I can search for supply purchases and A&E firms that did unusual design and fabrication contracts.”

“Don’t you think that the government is already doing that?” asked Ortiz. “What makes you think you can succeed where they, with all their resources, haven’t?”

Townsend smiled. “Partly, it’s because I have faith in my own ability. I see things a little differently than most people—some indefinable difference in perspective, I guess. Whatever it is, a sixth sense, or subliminal knowledge, or some weird instinct—it has always found a way. Secondly, there is a lot of confusion about these people. What drives them—what their ultimate goals are. I have opinions about that too. You don’t set a thief and scoundrel to fathom the motivations of a priest or a patriot. That’s just an analogy, but you get my meaning. One can’t fathom the thinking of the other, not in any real way.

“The government is looking at this in a military sense, like it was a militant faction, even a splinter force that broke off some army, somewhere, or like a rival mob that wants to take turf away from their gang. I think they’re all wrong.”

“Who do you think it is?” Ortiz asked.

“I think it’s a group of scientists,” Townsend replied, “or at least, a group composed mostly of scientists and engineers. Technical people, not military types. Their motives are altruistic, pure and simple. They have the physical institutions necessary to hide the acquisition of supplies and materials. The research could be broken up into a thousand pieces and piggybacked onto other, diverse research projects over a period of time, and no one would ever be the wiser.”

Ortiz picked at his fingernails. “Sounds reasonable,” he said.

“I’m convinced of it, Dr. Ortiz,” Townsend said, studying the old scientist. “All that remains is to analyze past research projects for anomalies in parts, materials and services. I’ll bet that these people used a lot of federal research grants as the piggyback vehicles to accomplish that weapon system. They probably laughed at the irony of it. Federal research grants require a lot of detailed record-keeping though, and I have access to those files.”

“Well, I’ll say this for you,” said Ortiz, meeting Townsend’s gaze, and smiling, “you’ve got the makings of a good detective yarn, or spy story. You’re likely barking up the wrong tree, though. Scientists are fundamentally humanitarians and environmentalists—tree-huggers and fern-feelers. They don’t make war, at least not directly.”

“One thing I’ve learned about life,” said Townsend, smiling back. “Given incentive, nature will produce a fluke. Man, animal or plant, if pressure is brought to bear, life will adapt, even if the adaptation is contrary to precedence.

“It’s an irony and a pity,” Townsend said, staring out the window introspectively, “every technological breakthrough has its yin and yang. Computers have revolutionized medicine, made space flight possible, helped us in a thousand ways, but they have also made a global, criminal network possible.

“The same holds true for this weapon. Right now, it appears to be a savior. If the Defense Department gets control of it, it will either be the ultimate whip to beat mankind into submission, or the ultimate shield of freedom. Whoever controls the Defense Department will decide which purpose it is put to.”

“Do you think they will get control of it?” Ortiz asked.

“I don’t know. I do know they intend to try. That’s another area where I can be useful.

“A few weeks ago something happened that made up my mind. As a precaution, I wrote a computer program, just an algorithm really, but it enables me to gain access to several different secure computer nets in the intelligence community, including most of the affiliated agencies and their contractors. The complexity of the federal network is also its greatest weakness.

“Anyway, I had authorized access, but I suspected that authorization might be limited or revoked by my supervisor at any moment. We had a philosophic

al disagreement of sorts, you might say. I couldn’t risk waiting until I was denied access, so I did it. As it turned out, it was none too soon; my department chief turned me out permanently. I’m a fugitive. Legitimate law-enforcement agencies are after me.”

“Why are you trusting me with this?” Ortiz asked. “You don’t know me.”

“Eddie says you feel the same way that I do. You are not going to help me without knowing why, are you?”

“No, but it seems like an all-or-nothing gamble on your part. I could turn you in.”

“Are you going to?”

Ortiz smiled, “Not today.”

“Will you help?”

“I have a friend who has some theories. I’ll let you talk to him on one condition. I want to know everything you intend to do, before you do it.”

“Why?”

“I have my reasons. Uppermost is self-preservation. Only a little below that is concern for the lives of the people that I put you in touch with. I’m sorry, but I can’t be as trusting as you. The Feds are well-known for entrapment schemes. There is too much at risk. For the moment, let’s just say that philosophically I might agree with your political views to some extent. I will help you, insofar as helping you to do some computer research. I won’t support any act of direct treason. That will have to suffice for now. Deal?” Ortiz extended his hand.

“Deal,” said Townsend, shaking hands. “Thanks, Dr. Ortiz.”

They stood up.

“Having someone like Eddie and you to talk to, makes me feel a little less alone,” said Townsend. “Your help means a lot.”

“Just call me Hector. I’ll see what I can do. We’ll meet somewhere else in the future, just to reduce the numbers of curious people watching us come and go, and to avoid the possibility of someone listening in, okay?”

“My thoughts exactly. Call you tomorrow.”

XXII

Gene Stickle sat with three other physicists in a conference room at the U.S. Army Strategic Defense Command’s headquarters in Huntsville, Alabama. Present were Able Johnson, a rangy, middle-aged Southerner from Georgia Tech University; Ted Wallace, a younger professor from Cal-Tech who, like Johnson, was a contract consultant to SDC; and Joe Mercer, a middle-aged government employee like Stickle, and past director of the SDC’s now defunct Directed-Energy Weapons Program.

Johnson and Wallace had worked independently of one another to perform a contracted study for SDL. Their task had been to assimilate and correlate all the detailed data gathered about the effects of the weapons beam and develop a theory regarding its operation and tactical weaknesses. Wallace had come up empty. Johnson was giving his report. Wallace doodled on a legal pad, listening, interjecting occasionally. Mercer and Stickle were attentive to Johnson, who was describing, in a rich, baritone drawl, his speculations on the technology of the weapon.

“I think it’s safe to assume,” he began, “that given the small size of the thing, that the energy beam is not just brute power. The weapon system’s not big enough. The power plant required to deliver a forty-terawatt beam to the earth’s surface would be big enough to blot out a big part of the moon. The mirror itself would have to be twelve meters in diameter to deliver a focused beam with a three-meter aperture at the earth’s surface. It would stand out in orbit like a spotlight. Since we know the weapon platform is not much over a meter in diameter, they must have used a small superconducting magnet array to focus and modulate the beam. It simply can’t handle that much power. Based on that assumption, I’ve tried a bit of computer modeling that leads me to believe that it must operate on the principle of resonance.

“The energy of the beam sets up a sympathetic vibration in materials, kind of like a microwave oven, at the molecular or atomic level. Maybe even the nuclear level. What was mystifying about the damn thing at first was that it seems to couple efficiently with a wide variety of materials. At any rate, resonant coupling could explain energy transfer ratios at sufficient amplitude to do what it does. The specific mechanism is not readily evident. I do have a hypothesis, though.”

“You hinted earlier that you’ve eliminated infrared wavelengths,” said Wallace. “The bandwidth at IR frequencies is certainly sufficient for high frequency modulation. There are only ten elements in the periodic table with nuclear magnetic resonance frequencies over one hundred megahertz. Hydrogen is the highest at three hundred megahertz. Seems to me a carbon dioxide laser could do it.”

“Ionization potential is too low at IR frequencies,” interjected Stickle. “It’s not simply a thermal effect.”

“I agree,” said Johnson. “It’s in the UV or X-ray spectrum. It doesn’t just heat things up until they melt or vaporize. You would be back to the objection of too big an energy requirement. No, this thing literally blasts things apart, and the thermal bloom we’ve seen in the satellite images is more of a side effect than a direct cause.”

“You mean, the breakup of the target material creates an exothermic chemical reaction, right?” said Mercer.

“Exactly,” responded Johnson. “I think it’s a form of induced fission.”

“Let’s come back to that in a minute,” said Stickle.

“What about the simple beam mechanics—control signals, feedback, and so on? Can we detect control signals, or targeting signals, and interfere with them? What kind of time do you think we have, from command initiation until it positions and fires?”

“Well, in my opinion, the uplink is as simple as shit, and there’s not a hell of a lot that you can do to interfere with it. They have probably located a few simple, low-powered, modulated lasers at various sites around the country. These are set up as dumb terminals, or slaves. They can be controlled by modem, by telephone, by radio—a dozen different ways. I’d bet they’re slaved to an active computer, somewhere.

“Multiple sites would insure that the weather can’t block a signal, and more importantly, that a stratospheric rocket can’t ionize the atmosphere with a seed chemical to disrupt ground-to-orbit communications. Any one of these lasers could send a hundred-nanosecond burst of digital data with target coordinates and a GO code. If you are them, and you’ve really been clever—and it seems to me that they have been, at every turn—you have several major firing events preprogrammed into the weapon’s fire control system. You add a well-known little device called a dead-man’s switch. The active computer I mentioned sends a signal pulse every so often to the weapon system’s fire control, telling it to dump its current countdown, and start over again. The computer has to be manually reset at regular intervals.

“That way, if you are captured, all you have to do is threaten not to reset the computer that controls the switch. After a certain amount of elapsed time, the damn thing begins to acquire targets and fire automatically.

“A word of advice in that regard, gentlemen. If you do catch them, you had better not let anything happen to them until that weapon system is disabled. If you kill them, or if they refuse to tell you the control codes, that thing could kill every plant, animal and human being in the northern hemisphere. It could sterilize half the earth, and maybe as a side effect, kill the entire planet.”

Johnson paused for effect. “Make no mistake about what you’re up against, gentlemen. It may be literally the annihilation—utter and complete—of all surface life on this planet.”

“Sweet Jesus,” uttered Mercer, “it just gets worse and worse.”

“No defense at all?” asked Stickle.

“The only survival possibility that holds any hope at all is deep undersea habitats with nuclear power systems,” said Johnson. “Deep mine shafts and such might work for a while, but you’ve got to understand that the atmosphere is not going to be breathable for years—maybe decades. You would have to come up with some way to produce food, water and oxygen, and to handle wastes.”

Johnson paused again, staring out the window into the distance. “God only knows what kind of weather patterns would eventually emerge. Look at what happened when it traced a thin

line—a mere two miles wide—up the east coast. Think about that land of energy and destruction crossing the breadth of the North American continent. It would probably sweep from east to west, like the shadow of a cloud passing over the earth. Everything the shadow touched would explode and burn. Even the bacteria in the soil would be destroyed. Dust and smoke in the stratosphere for ages, blocking sunlight. Nothing could grow. Onset of an ice age. The planet climatology might never recover.”

“Maybe the Doomsdayers are right,” said Mercer, despondently. “Maybe that damned thing really is the Sword of God.”

“Maybe,” said Johnson reflectively. “At any rate, living in the sea has the advantage that the water volume of the oceans provides an enormous buffer system. The food chain will suffer, and plankton and other life will be affected, but the polar caps are likely to suffer somewhat less. Fish, shellfish and various sea flora should be available for years, and breathing oxygen can be liberated from sea water by electrolysis or chemical reaction. Hydrogen too, for combustion processes, and for power production and light. The sea bottom can be farmed if you have light, and wastes are easily handled—they’re even useful as fertilizer.”

“I confess, I hadn’t followed it out as far as you have, Dr. Johnson,” said Stickle. “I guess we really are looking at a potential doomsday scenario. The people we work for certainly haven’t thought that far ahead. They see this simply as a power struggle, a king-of-the-mountain game. I’m wondering what they will say when I present your findings.”

“I doubt it will slow them up very much,” said Wallace. “Most people don’t know that many of the reputable scientists that built the first atomic bomb—the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, during the Second World War—were afraid that it would set the atmosphere on fire and destroy the world. They wanted to stop the project. Maybe that’s why they called it the Trinity Site, where it was tested. At any rate, they did it anyway. They took the chance, and risked all of humanity. That ought to tell you something about power-mad politicians.”

Operation Damocles

Operation Damocles